On Essays in General

Contents

- Thirty-Six Ways of Looking at an Essay;

- "Ars Poetica and the Essay" and Other Writing about the Essay Form;

- On the History and Nature of the Essay;

- Reading Essays and Reading About Essays;

- Examples;

- Serial Literature;

- Reference;

- Critical Studies;

- Practical Guides;

- Electronic Resources;

- Individual Essayists.

~ Thirty-Six Ways of Looking at an Essay ~

The following extract and list are taken from “Thirty-Six Ways of Looking at an Essay,” which forms the Afterword (pp.237-241) in Hummingbirds Between the Pages.

“Considering the essay through the multiple lenses suggested in this short Afterword will, I hope, help to promote a more enlightened view of the possibilities offered by this form of writing. Too often, essays are confused with academic assignments or associated with a form of belles-lettres that has had its day. It’s a great shame that what Robert Atwan described twenty years ago as ‘our most dynamic literary form’ (in his Foreword to The Best American Essays 1997) continues to be dogged by these powerful misconceptions. They have resulted in too many people dismissing the essay as something of little interest that languishes in a literary dead-end, or that’s confined to the academic backwaters of student assessment.”

The thirty-six views offered are intended to counteract such commonly encountered misperceptions of the genre.

Note the author’s warning: “The essence of the genre — if it has an essence — can’t be captured in thirty-six views, still less in any single definition. This is a richly protean literary form; by nature it’s resistant to attempts at systematization or regulation. Even if my thirty-six views were multiplied tenfold, it still wouldn’t give a perfect 360-degree perspective that ringed the essay round, containing it within a stockade of complete control and circumscription. Such multiple efforts, like the thirty-six I’ve offered, would simply lay down more paths of meandering circumambulation. These might reveal further nuances, angles, aspects, currents, emphases, features, trends and tendencies — but they could never completely contain or encapsulate the essay. It will always remain possible to create another view. The more views we can formulate and consider, the better chance we have of deepening our appreciation of this mercurial mode of writing”.

1. An essay richly complicates the commonplace, revealing mazes of meaning coiled within the mundane.

2. An essay is a net for catching butterfly moments as they fly past us; it allows us to examine them more closely.

3. An essay remains true to its etymological springs — essai, essayer, assay (attempt, experiment, weigh up, test, investigate) — p even though its waters have flowed far beyond them.

4. An essay is a listening device that allows us to hear extracts from the music playing in another person’s head.

5. An essay is a way of carving out with words some semblance of the things that have caught the essayist’s attention.

6. An essay picks out threads of meaning from the fabric of existence.

7. An essay is a borehole in the dry dirt of the ordinary. When it works, it floods us with unexpected artesian water.

8. An essay seeks its quarry from the herds of ideas wandering the mind’s savannahs.

9. An essay interrupts the silence with an individual’s voice speaking briefly, intimately about what it’s seen.

10. An essay is a verbal lens ground and polished to the focal length of a particular personality’s outlook.

11. An essay is a report from the crow’s nest of the self; it tells us about the view and the viewer.

12. An essay attempts in words what a mind attempts in thoughts.

13. An essay records a beachcomber’s finds as s/he wanders a particular stretch of time’s shoreline.

14. An essay constructs permeable enclosures through whose word-walls momentarily captive ideas can freely pass and intermix.

15. An essay is a short prose track that simultaneously leads into the mind of the essayist and whatever aspect of the world that mind is engaged with.

16. An essay is as far removed from a scholarly article as a sonnet is from a butcher’s cleaver.

17. An essay is poetic prose tuned to follow the gradients of the essayist’s experience, close-shadowing the twists and turns of thought and feeling. It is a p contour map of consciousness in words.

18. An essay is a considered composition that applies the high polish of fluency to the raw inarticulacy of immediate impressions.

19. An essay does in words what music does in notes.

20. An essay is an extended signature spelling out the essayist’s name and identity.

21. An essay arranges words with one eye on sense, one eye on style, and a third eye on wisdom.

22. An essay is a literary electrocardiogram that traces out in words the pulse of thoughts.

23. An essay knocks the flints of words together over the tinder of experience and blows on the sparks.

24. An essay’s short filaments of prose shine the light of reflection into overlooked places.

25. An essay eavesdrops on consciousness.

26. An essay leaves a fractional record of one individual’s fleeting moments of being.

27. An essay is a distillation of one voice; it offers at a higher proof than the liquor of ordinary diction what might be said in conversation between p friends.

28. An essay is a carefully worked prose map whose lines and shadings show aspects both of the landscape under scrutiny and of the scrutinizing cartographer.

29. An essay casts word-bait on the mind’s waters and sometimes gets a bite.

30. An essay pulls into the light of attention commonplace things that are generally consigned to the dusk of being scarcely noticed.

31. An essay is a path, usually meandering, to a false summit from which higher peaks can always be seen.

32. An essay is a fragment of prose infused with ideas and individuality.

33. An essay isn’t amenable to definition or summary, doesn’t follow a blueprint of progression and may not arrive at any clear conclusions; it leans more p toward heresy than orthodoxy, prefers meanders to straight lines, favors digression, eccentricity — and yet is lucid, focused and well planned.

34. An essay tries to lure verbal coherence out of the chaos of experience.

35. An essay opens veins in the body of meaning and writes with what bleeds from them before the clots of convention form.

36. An essay is a witness statement that testifies to what it’s like to be alive.

"Ars Poetica and the Essay" and Other Writing about the Essay Form

Irish Nocturnes, Irish Willow, Irish Haiku, Irish Elegies, Words of the Grey Wind, and On the Shoreline of Knowledge all contain some reflections in their opening pages about the nature of essays and essay writing. Comment on the genre can also be found in "An Essay on the Esse" (in Irish Elegies). In March 2015, in a piece written for World Literature Today, Chris Arthur offered some further ideas about the art of essay writing, using Archibald MacLeish's poem "Ars Poetica" as a touchstone.

"Ars Poetica and the Essay" is available here.

Further reflection on the nature of this form of writing is given in two 2017 pieces, "A Blind Spot in the Ornithology of Letters" (which looks at the absence of the essay in schools and universities, where it's routinely confused with academic assignments) and "An Irish Essay(ist)?" (which considers national traditions of essay writing).

From "A Blind Spot in the Ornithology of Letters"

... Although academia prides itself on accuracy, precision, the ability to classify, define, and apply correct terminology, there's a curious blind spot when it comes to "essay". It's a label that's carelessly attached to almost any short piece of nonfiction writing. I don't dispute that essays and assignments share some common features, anymore than I'd deny that albatrosses and hens do. The problem is that a bizarrely indiscriminate ornithology of letters has taken root, leading to dissimilar species being confused. Worse, the prevalence of a common one risks threatening the very existence of what's become a rarity.

From "An Irish Essay(ist)?"

... I hope my essays will be judged not on the basis of my ethnic identity, but on their quality as pieces of imaginative writing. My loyalties as an author, such as they are, lie more with a genre than with any country. I may no longer feel at home in the world in terms of a place that I can call my own, a nation to which I could give unqualified allegiance, but I do feel at home in the territory of the essay. Citizenship of that territory is not determined by the accident of birth, or by religion, language, or ethnicity, but by a simple test of disposition. This is well summed up by one of the key modern authorities on the form, Graham Good: "Anyone who can look attentively, think freely, and write clearly can be an essayist; no other qualifications are needed." It doesn't matter if you're Irish, British, American, Chinese, French, Kenyan or Peruvian; it doesn't matter if you're Catholic or Protestant, Hindu, Jew, or atheist; it doesn't matter if you write in English, Cantonese, Arabic or Polish; your age, gender, color, sexuality is irrelevant — the essay's criteria of belonging are the same for everyone.

On the History and Nature of the Essay

In 2008, Chris Arthur took part in a Summer School at the University of Wales, Lampeter (other keynote speakers included poet, playwright, novelist and librettist Michael Symmons Roberts). This is an extract from the first of Arthur's lectures, "Defending Loose Sally's Honour: An Introduction to the Fourth Genre."

... "As I'm sure most of you will have guessed, my "Loose Sally" doesn't refer to some dubious lady of the night. The name comes from a definition that appears in Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language. In this great work, first published in 1755, Johnson described a particular type of writing as being "a loose sally of the mind". It's this type of writing that I wish to champion — or, I should say, what this type of writing has evolved into two and half centuries after Johnson so defined it.

I wish I could avoid for longer the common name given to what Johnson defined in this way, but I don't think I can without being tortuously indirect. He was speaking about the essay. Unfortunately, "essay" carries so many negative associations that the word can't be used without qualification. On its own, it acts as a kiss of death in terms of attracting readers. I imagine it can have a similarly toxic impact on an audience. Too many people equate "essay" with the assignments they had to do at school or university. If it's not stuck in the classroom, the essay often gets locked into a kind of bizarre time warp. This imprisons it somewhere in the Edwardian era as a kind of genteel prose pastime written by people who have little else to do. Graham Good — one of the best contemporary commentators on the genre — offers a depressingly accurate caricature of how "essayist" and "essay" still so often strike people. These words, he says,

"Conjure up the image of a middle-aged man in a worn tweed jacket in an armchair smoking a pipe by a fire in his private library in a country house somewhere in southern England, in about 1910, maundering on about the delights of idleness, country walks, tobacco, old wine and old books, blissfully unaware that he and his entire culture are about to be swept away."

This type of essay — miles removed from the vigorous, edgy, unconventional and challenging writing being done in the genre today — is witheringly characterized by Ian Hamilton as the "something-about-next-to-nothing school" involving "virtuoso feats of pointless eloquence." Unless the deadwood of these outmoded connotations can be got rid of, "essay" just sounds tedious.

... Today's essays stem from a confluence of many tributaries, the sources of which are not always clear, nor is it easy to map their meanderings or determine where one river of words merged with another in the great watercourse of prose in which our wordy species swims. Montaigne (1533-1592) is usually presented as the inventor of this form, with Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626) named as its originator in English — leading on to that famous duo of periodical essayists, Joseph Addison (1672-1719) and Richard Steele (1672-1729) — and from them, in various leaps and bounds (Johnson, Goldsmith, Lamb, Hazlitt, Carlyle, Thackeray, Stevenson, Belloc, Chesterton) to Woolf and Orwell, with whose contributions histories of this particular vein too often stop, as if the genre was now of merely historical interest.

This genealogy, whose rosary of famous names I've just recited, is, I'm afraid, of highly dubious legitimacy. As Terence Cave has recently argued, there's a world of difference between Montaigne's "essais" and Lamb's "essays". I'm not at all convinced that contemporary "creative nonfiction" ("a singularly unlovely and antiseptic term", according to Rachel Blau DuPlessis) could trace its bloodline back to Addison and Steele, or that it would want to. In any case, I'm more interested in writing essays than in tracing their literary ancestry, or in finding a name for the genre which is less embedded in misconception and negative connotation.

Sir Richard Steele (1672-1729), incidentally, the Irish writer who had such an impact on the English essay, and who has sometimes been called "the father of journalism" died not far from here. Eight years ago, somewhat gruesomely, work on levelling the floor of St Peter's Church Carmarthen turned up Steele's skull. Perhaps we should have organized a field trip! There's a good article about the find, which also provides some background on Steele, in The Guardian.

Whatever conclusions we reach about the provenance of the essay, when we're thinking about its origin and development we need to remember that the Western perspective is only one, and the English essay is not its sole representative. In his book on and entitled The Chinese Essay (2000), David Pollard includes examples from the work of essayists who lived centuries before Montaigne. Looking to the Classical world, we can also point to proto-essayists in figures like Cicero, Plutarch and Seneca. There are many national traditions of essay writing. The French essay, the English essay and the American essay are particularly rich seams in the deposits of this genre, but they are by no means the only ones. Scholars can identify key figures along the way and plot out how they've influenced each other, they can categorize essays into types — the personal essay, the nature essay, the medical essay and so on — but it's impossible to be sure when or where this form first emerged or what its boundaries are. It surely existed before it was so named, and did so simultaneously in different places in different forms. This is not a genre with any single point of origin, neatly circumscribed characteristics or clearly demarcated territory. Though there are some crucially important wellsprings — most obviously Montaigne — who's to say which shard of prose, in which language, in which century constitutes the original ur-essay that set the standard for its descendants to follow? Following a set pattern is, in any case, alien to this type of writing. R. Lane Kauffmann refers to the "skewed path" that essays follow, and to their "unmethodical method." Graham Good talks about "the essay's multiplicity of forms," its "spontaneity, its unpredictability, its very lack of a system." This is a fugitive and unpredictable genre. It prefers the margins to the mainstream, it eschews conformity. It's what William Gass terms a "watchful" form, inclined more to scepticism, dissent and heresy than to any literary orthodoxy.

However questionable the lineage may be, many essayists do claim Montaigne as forbear and there's no doubt that the sense he attached to the word "essai" in 1580 still potently influences the sense in which many practitioners of the form understand it today. And of course his work continues to impress. I was pleased — what essayist wouldn't be? — when one reviewer suggested that I was "a worthy inheritor of the tradition of Montaigne" — though I'm far from convinced I actually deserve this compliment. "Essai" for Montaigne meant "a trial or attempt", and it's the experimental nature of the genre that gives it much of its appeal, the way it allows one to try things out. It offers no set procedure. It is, rather, a style of wondering and wandering in prose that tolerates massive variation in length, in language and in subject matter. As Carl Klaus puts it, "the essay is an open form" which "gives a writer the freedom to travel in any direction." As Lydia Fakundiny says — in The Art of the Essay (1991) — it "obeys no compulsion to tie up what may look like loose ends;" it "tolerates a fair amount of indeterminacy;" it "steers away from logically ordered sequences of elaboration." There's no pretence at closure or conclusion. Essays are sympathetically fragmentary, as inchoate as our lives are.

Essays are rooted in what passes, rather than in what's invented; focused on aspects of "the real world" rather than on what's made up. They're interested in following the contours of reality rather than creating any fictive landscapes. But essayists are not engaged in some kind of naively realist descriptivism. They're alert to the fallibility of perception, memory and expression; to the partiality of personality, the fact that language is not a simple verbal mirror of what is but that it imports its own cargoes into every image. They recognize that their truth-telling happens through the complicated lenses of subjectivity. Robert Atwan touches on some of these issues when he reminds us that "personal", the word we use to convey intimacy and sincerity, has "hidden overtones of disguise and performance", its roots going back to the Latin "persona" which meant "mask". Essayists, as Atwan notes, "know that the first-person singular is not a simple unmediated extension of the self, that the 'I' of the sentence is not always the same as the 'I' who wrote the sentence."

The freedom and flexibility of essays is what most appeals to me about this genre. I'm also drawn to their tradition of individuality, their scant regard for authority and their love of language. I think Graham Good is quite correct when he says that: "At the heart of the essay is the voice of the individual". This voice is very different from the one that speaks in the machine-like prose we generate for reports and articles — the kind of writing that eschews subjectivity, aiming instead for bland neutrality. Such prose is carefully gutted, the innards of feeling taken out, supposedly leaving only the lean muscle of objectivity. Every trace of the "I" is exorcised; the words are purged of any taint of the individual. In contrast, essayists draw on the personal with all its idiosyncratic passions and puzzles. It's a hard form to define and I'm not going to try — in fact I'd agree with Douglas Atkins that essays represent "an implicit critique of the drive towards definition." A final reason why I like this genre before proceeding with some readings: Alexander Smith once said that essays are concerned with "the infinite suggestiveness of common things." I'm drawn to the everyday epiphanies such suggestiveness sparks and like the freedom essays offer for exploring them."

© Chris Arthur 2008

Reading Essays and Reading About Essays

"Writing is the monumentally complex operation whereby experience, insight, and imagination are distilled into language; reading is the equally complex operation that disperses these distilled elements into another person's life. The act only begins with the active deciphering of the symbols. It ends (if reading can be said to end at all) where we cannot easily track it, where the atmospheres of self condense into thought and action ... The writing process begins in the writer, the life; but it branches off into paper, into artifice; but the final restless resting place of every written thing is the solitary life of the reader. There it hibernates, a cluster of stray images, forgotten incitements and conversational asides, a mass of shadow wrapping itself around the thoughts and gestures of the self."

Sven Birkerts, The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in An Electronic Age (Faber, New York: 1994), pp.96 & 108

Examples

A good way to get a sense of the richness and diversity of this type of writing is to read the 30+ volumes of Robert Atwan's The Best American Essays. These offer intelligent introductions and a rich annual anthology that gathers material from a range of America's premier literary journals. (The series has been published since 1986 under Atwan's direction as series editor, but with a different guest editor each year. Published by Ticknor & Fields up to 1993 and by Houghton Mifflin from 1994 to date.)

The best single-volume anthologies are Lydia Fakundiny's The Art of the Essay (Houghton Mifflin, Boston: 1991) and Phillip Lopate's The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present (Doubleday/Anchor, New York: 1994). Both contain selections that include classic examples of the genre and some less expected candidates. Both provide intelligent commentary. Fakundiny's volume is particularly useful because of her introduction, "On Approaching the Essay", which gives a brilliant characterisation of the form. Her sections on "Montaigne and the Essay" and "Essayists on Their Art" are also good.

Other anthologies worth noting are: John Gross's The Oxford Book of Essays (1991); Ian Hamilton's Penguin Book of Twentieth Century Essays (1999); Carl Klaus, Chris Anderson & Rebecca Faery's In Depth: Essayists for our Time (1990); Bill Roorbach's Contemporary Creative Nonfiction: the Art of Truth (2001); and John D’Agata’s trilogy: The Next American Essay (2003), The Lost Origins of the Essay (2009), and The Making of the American Essay (2016), all published by Graywolf Press, Minneapolis. A composite volume containing all three anthologies, A New History of the Essay, also appeared in 2016, edited and introduced by John D’Agata, and with a Foreword by James Wood.

The approach that D’Agata takes in his anthologies has attracted strong criticism from William Deresiewicz. According to Deresiewicz, D’Agata’s project is one “that misrepresents what the essay is and does, that falsifies its history, and that contains, among its numerous selections, very little one would reasonably classify within the genre.” He argues that “for the self-appointed curator of an entire genre, D’Agata shows a stunning paucity of literary judgment.” Deresiewicz’s robust critique, “In Defense of Facts,” first appeared in the January/February 2017 issue of The Atlantic (pp.90-99), with the strapline “A new history of the essay gets the genre all wrong, and in the process endorses a misleading idea of knowledge.”

The books listed above contain ample evidence, if evidence is needed, to back up the claim made by Robert Scholes, Nancy Comley, & Carl Klaus that the essay should be regarded, alongside drama, poetry and fiction, as one of the four basic forms of literature (see their Elements of Literature, 4th edition (1991), p.xxvii).

Serial Literature

Further examples of the genre with right up-to-the-minute examples of contemporary writing can be found across a wide range of literary journals. Again, Robert Atwan's The Best American Essays is a key resource, not only in terms of the work it anthologises, but for its annual list of "Notable Essays" of the year. This list can be used to identify which journals are publishing material of this type.

Some journals are exclusively concerned with creative nonfiction, for instance Creative Nonfiction, edited by Lee Gutkind, which started publication in 1993, or Fourth Genre, or River Teeth. Arguably the most interesting essays appear in journals with mixed content (e.g. Southwest Review, Southern Humanities Review). In terms of contemporary Irish literature, Dublin Review and Irish Pages increasingly feature work in this genre.

Both Fourth Genre and Creative Nonfiction have published anthologies which offer a selection of material drawn from the journals. See Lee Gutkind (ed.) In Fact: The Best of Creative Nonfiction (W.W. Norton, New York: 2005) and Martha A. Bates (ed.) 5 Years of the 4th Genre (Michigan State University Press, East Lansing: 2006).

Reference

The key reference work in this area is Encyclopedia of the Essay, edited by Tracy Chevalier (Fitzroy Dearborn, Chicago & London: 1997, reprinted 2001). It's interesting that the editor went on to write Girl with a Pearl Earring, published in 1999, a book that merges fact and fiction in some fascinating ways.

Graham Good, one of the team of editorial advisers, begins his preface to this volume thus: "An encyclopedia of the essay sounds at first like a paradoxical enterprise: how can the essay's elusive multiplicity of forms and themes be contained within the systematic scope of an encyclopedia? The essay is often characterized by its spontaneity, its unpredictability, its very lack of system. Yet precisely these qualities have made it the little noticed (though much practiced) of the literary genres, and hence the most in need of some kind of comprehensive guide. Of course there can be no complete mapping of such a diverse literary form: to define all of its varieties and enumerate all its practitioners would take a much larger volume than this. Nevertheless, Encyclopedia of the Essay does bring together the essential information for exploring this protean form of writing." (p.xix)

Critical Studies

In the small selection that follows, works by Aquilina, Cowser & Wallack, Bakewell, Butrym, Chadbourne, and Good are particularly recommended:

- Mario Aquilina (ed.), The Essay at the Limits: Poetics, Politics and Form (Bloomsbury Academic, London: 2021)

- Mario Aquilina, Bob Cowser Jr, & Nicole B. Wallack (eds), The Edinburgh Companion to the Essay (Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh: 2022)

- G. Douglas Atkins, Estranging the Familiar (University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA: 1992)

- G. Douglas Atkins, Tracing the Essay: Through Experience to Truth (University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA: 2005)

- G. Douglas Atkins, Reading Essays: An Invitation (University of Georgia Press, Athens GA: 2008)

- Sarah Bakewell, How to Live: A Life Of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (Chatto & Windus, London: 2010)

- Bruce Ballenger, Crafting Truth: Short Studies in Creative Nonfiction (Longman, Pearson Education Inc: Boston etc.:2011)

- Alexander J. Butrym (ed.), Essays on the Essay (University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA: 1989)

- Richard M. Chadbourne, "A Puzzling Literary Genre: Comparative Views of the Essay", Comparative Literature Studies, Vol.20 no.1 (1983), 131-153

- Rachel Blau Duplessis, "f-Words: An Essay on the Essay", in American Literature Vol.68 no.1 (1996), pp.15-46

- Patricia Foster & Jeff Porter (eds.), Understanding the Essay (Broadview Press, Peterborough: 2012)

- Graham Good, The Observing Self: Rediscovering the Essay (Routledge, London: 1988)

- Thomas Karshan & Kathryn Murphy (eds), On Essays: Montaigne to the Present (Oxford University Press, Oxford: 2020)

- Carl H. Klaus, The Made-Up Self: Impersonation in the Personal Essay, (University of Iowa Press, Iowa City: 2010)

- Carl H. Klaus and Ned Stuckey French (eds.), Essayists on the Essay: Montaigne to Our Time (University of Iowa Press, Iowa City: 2012)

- David Lazar & Pat Madden (eds.), Covering Montaigne: Contemporary Essayists Cover the Essays (University of Georgia Press, Athens GA: 2015)

- Claire de Obaldia, The Essayistic Spirit: Literature, Modern Criticism, and the Essay (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1995)

- Brian Dillon, Essayism (Fitzcarraldo Editions, London: 2017)

Note: Essayism doesn’t fit neatly in the category of “Critical Studies”. The cover blurb on Brian Dillon’s fascinating book puts the matter well: “Essayism is a personal, critical and polemical book about the genre, its history and contemporary possibilities. It’s an example of what it describes: an essay that is curious and digressive, exciting yet evasive, a form that would instruct, seduce and mystify in equal measure. Among the essayists to whom he pays tribute — from Virginia Woolf to Georges Perec, Joan Didion to Sir Thomas Browne — Brian Dillon discovers a path back into his own life as a reader, and out of melancholia to a new sense of writing as adventure.”

Practical Guides

In A Poetry Handbook (Harcourt, Inc., San Diego: 1994, p.10) Mary Oliver says:

But, to write well it is entirely necessary to read widely and deeply. Good poems are the best teachers.

The point she’s making holds for essays too. Those who wish to write in this genre are well advised to read widely and deeply in it. Essays, rather than books about essay writing, are the best teachers.

An invaluable source of good essays is The Best American Essays series, published annually since 1986 (under the general editorship of Robert Atwan — until 2023 — and with a different guest editor each year).

Also worth noting are Phillip Lopate’s anthologies: The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology form the Classical Era to the Present (1994); and his more recent trilogy: The Glorious American Essay: One Hundred Essays from Colonial Times to the Present (2020), The Golden Age of the American Essay 1945-1970 (2021) and The Contemporary American Essay (2021).

As noted above, Lydia Fakundiny's The Art of the Essay (Houghton Mifflin, Boston: 1991) is also recommended – not only for the essays it contains, but for the editor’s excellent introduction.

Practical guides, of varying quality, that seek to foster writing in this genre include:

- Sheila Bender, Writing Personal Essays: How to Shape Your Life Experiences for the Page (Writer's Digest Books, Cincinnati: 1995)

- Lynn Z. Bloom, Fact and Artifact: Writing Nonfiction (Prentice Hall/Blair Press, Boston: 1994)

- Victoria Chang, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief (Milkweed Editions, Minneapolis: 2021)

- Philip Gerard, Creative Nonfiction: Researching and Crafting Stories of Real Life (Story Press, Cincinnati: 1996)

- Vivian Gornick, The Situation and the Story: The Art of Personal Narrative (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, New York: 2002)

- Lee Gutkind, The Art of Creative Nonfiction: Writing and Selling the Literature of Reality (Wiley, New York: 1997)

- Brenda Miller, A Braided Heart: Essays on Writing and Form, (University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor: 2021)

- Stephen Minot, Literary Nonfiction: The Fourth Genre (Prentice Hall, New Jersey: 2003)

- Dinty W. Moore, Crafting the Personal Essay: A Guide for Writing and Publishing Creative Nonfiction (Penguin Random House, New York: 2010)

- Robert Root & Michael Steinberg, The Fourth Genre: Contemporary Writers of/on Creative Nonfiction (Longman, New York: 2001)

- Bruce Ballenger, Crafting Truth: Short Studies in Creative Nonfiction (Longman, Pearson Education Inc: Boston etc.:2011)

- Sara Haslam & Derek Neale, Life Writing (Routledge, London: 2009)

- Brenda Miller & Suzanne Paola, Tell it Slant: Writing and Shaping Creative Nonfiction (McGraw-Hill, New York: 2005)

- Sondra Perl & Mimi Schwartz, Writing True: The Art and Craft of Creative Nonfiction (Houghton Mifflin, Boston: 2006)

Electronic Resources

Naturally, the Internet offers rich material on the essay — the problem lies in finding it! Putting "essay" into a search engine merely results in a ream of references to essay-writing services for students, very little on the essay form as a literary genre. Searching under “art of the essayist,” or "Montaigne," or "essai" (rather than essay) sometimes helps.

What follows is not a regularly updated — still less comprehensive — list, but at the time of writing these sites contained useful material:

- Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies — edited by Karen Babine and others. Its goal is "to test and analyze the nonfiction texts we read". The journal's philosophy is further outlined via a quote from Paul Gruchow: "There is no brief way to know a place even so small as this. Places can be claimed but never conquered, assayed but never fathomed, essayed but never explained. You can only make yourself present; watch earnestly, listen attentively, and in due time, perhaps, you will absorb something of the land. What you absorb will eventually change you. This change is the only real measure of a place." The Assay site suggests that "'nonfiction' could be substituted for 'place' and the ideas will still apply."

- Creative Nonfiction, edited by Lee Gutkind, not only publishes work in this genre, it also contains material about it.

- essaydaily.org, edited by Ander Monson, "is a space for ongoing conversation about essays & essayists of note, contemporary and not-so-much. We mostly publish critical/creative (not to say academic, necessarily) engagements with interesting essays (text and visual), Q&As with essays or essayists, and reviews of essays, essay collections or book length essays, or literary journals that publish essays".

- Michigan University Press's excellent Fourth Genre: Explorations in Nonfiction is “a journal devoted to publishing notable, innovative work in nonfiction. Given the genre’s flexibility and expansiveness, we welcome a variety of works ranging from personal essays and memoirs to literary journalism and personal criticism. The editors invite works that are lyrical, self-interrogative, meditative, and reflective, as well as expository, analytical, exploratory, or whimsical. In short, we encourage submissions across the full spectrum of the genre. The journal encourages a writer-to-reader conversation, one that explores the markers and boundaries of literary/creative nonfiction.”

- Quotidiana is principally the brainchild of Patrick Madden. He and his collaborators have assembled various conference papers, bibliographies and interviews with contemporary essayists, together with an extensive anthology of classical essays.

Individual Essayists

Listings here will vary enormously depending on which areas are selected for examination within the broad territory of the essay/creative nonfiction and, within the chosen area(s), which individual writers are then highlighted.

There are many different ways of mapping the various topographies within the genre's diverse territory. For instance, one could proceed nationally (English essay, French essay, American essay etc). As Richard Chadbourne points out, as well as "a surprising amount of agreement" concerning the nature of the genre, "each national essay tradition has its peculiar emphasis" ("A Puzzling Literary Genre: Comparative Views of the Essay", Comparative Literature Studies Vol.20 no, 1 (1983), p.149). The Encyclopedia of the Essay, edited by Tracy Chevalier (and with Chadbourne as one of the team of specialist advisers) offers one possible starting point for exploring the "peculiar emphasis" of national traditions, with articles on the American, Australian, British, Canadian, Chinese, French, German, Polish, Portuguese, Russian and Spanish essay. It's also interesting to look at nationally based anthologies - for example The Oxford Book of Latin American Essays (edited by Ilan Stavans) or The Oxford Book of Australian Essays (edited by Imre Salusinszky), both published in 1997.

That it is not always straightforward to place individual essayists within their "home" national tradition is something stressed by John Wilson Foster in his Foreword to Chris Arthur's Words of the Grey Wind:

"Ireland, of course, has produced its quota of essayists, from Oliver Goldsmith through (among others) Thomas Davis, Robert Lynd, Thomas Kettle, Stephen Gwynn and Filson Young to Hubert Butler. But if Lynd can be regarded as the Irish exponent par excellence of the English essay, it's clear that Arthur belongs to some other tradition, if he is not sui generis. His thought-processes are too unconfined, his subjects at once too spacious and narrowly focused, his procedure too conceptually chaste, and his intention too severely tasking, for the English essay."

Foster points to possible parallels with Octavio Paz or Gaston Bachelard. Is there an identifiable type of Irish essay? If so, in what ways does it differ from the English essay? Though there are, of course, numerous anthologies of Irish poetry, there is no Oxford (or similar) Book of Irish Essays. It is interesting to speculate what the contents of such a volume might be.

John Eglinton's Anglo-Irish Essays (The Talbot Press, Dublin: 1917) might make one ask whether, within the broad category of "Irish" essays, one might discern various "ethnic" types (Celtic, Ulster, Anglo-Irish). It could also be argued that in a twenty-first century context, instead of talking in terms of the American, Australian, Canadian, English and Irish essay traditions, it might make more sense to consider how "the essay in English" is informed by a whole welter of influences in a richly pluralistic globalized culture.

However the Irish essay is mapped, a prominent place needs to be given to Hubert Butler (1900-1991). Dublin's Lilliput Press published four of Butler's collections: Escape from the Anthill (1985), The Children of Drancy (1988), Grandmother and Wolfe Tone (1990) and the posthumously published In the Land of Nod (1996). Penguin brought out a selected essays volume in 1990, The Sub-Prefect Should Have Held His Tongue, and Butler was introduced to the American market in 1996 with a selection of essays entitled Independent Spirit (edited by Elizabeth Sifton and published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux). Irish Pages published a collection of essays on Hubert Butler in 2003 - Unfinished Ireland, edited by Chris Agee, and The Irish Pages Press also brought out a new selection of Butler’s essays in 2016, Balkan Essays by Hubert Butler. Reviewing Irish Willow in the Canadian Journal of Irish Studies (Vol.30 no.1 [2004], pp.86-87) Denis Sampson is one of several critics to compare Butler and Arthur. He comments: "Hubert Butler is his nearest kin in the field of Irish writing, a figure largely neglected for most of his writing life; it is to be hoped that the genre Arthur has chosen will not cause his unique body of work to be similarly neglected."

Some further ideas about national traditions in essay writing, with particular reference to Ireland, can be found in “An Irish Essay(ist)?”

Instead of proceeding by country, the extensive, sometimes confusing, territory of the essay might also be mapped chronologically (eighteenth century essayists, contemporary essayists), or according to type (autobiographical essay, medical essay, personal essay, travel essay, familiar essay etc).

"Nature Writing" is one particularly interesting sub-genre. As well as essays by such writers as Annie Dillard, Elizabeth Dodd, Edward Hoagland, Reg Saner, there are some book-length pieces of prose in this area bearing some intriguing similarities to the essay form. Examples here might include: J.A. Baker, The Peregrine (1967); Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1975); Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams: Imagination and Desire in a Northern Landscape (1986); Helen Macdonald, H is for Hawk (2014); James Macdonald Lockhart, Raptor: A Journey Through Birds (2016); and, from an Irish perspective, Michael Viney's A Year's Turning (1996).

Two brilliant examples of essay writing that don't fit easily into any of the categories suggested above are:

Simon Leys, The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays (New York Review Books, New York: 2013)

Neil MacGregor, A History of the World in 100 Objects (The British Museum, in conjunction with the BBC, published by Allen Lane, London: 2010)

"Linear thinking takes the article as form, nonlinear the essay."

G. Douglas Atkins

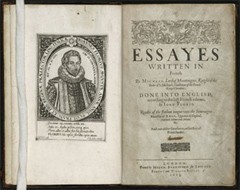

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) is often seen as the father of the essay. Nietzsche said of him, "That such a man has written adds to the pleasure of having lived on earth."

John (or Giovanni) Florio (c 1553-1625) was Montaigne's first translator into English. Born in England of Italian parents, Florio became Professor of Italian and French at Oxford. His first translation of the Essayes appeared in 1603. This picture shows his revised edition, published in 1613.

Quotes

The apt quotation is one of the essayist's greatest gifts.

William H. Gass, Habitations of the Word, Cornell University Press, Ithaca: 1985, p.28

Of all literary forms the essay most successfully resists attempts to pin it down.

O.B. Hardison, "Binding Proteus: An Essay on the Essay", in Alexander J. Butrym (ed.) Essays on the Essay: Redefining the Genre, University of Georgia Press, Athens GA: 1989, p.11

The essay is a brief, highly polished piece of prose that is often poetic, often marked by an artful disorder in its composition, and that is both fragmentary and complete in itself, capable both of standing on its own and of forming a kind of 'higher organism' when assembled with other essays by its author. Like most poems or short stories it should be readable at a single sitting; readable but not entirely understandable the first or even second time, and re-readable more or less forever ... the essay, in other words, belongs to imaginative literature.

Richard M. Chadbourne, "A Puzzling Literary Genre; Comparative Views of the Essay", Comparative Literature Studies, Vol.20 no.1 (1983), p.149/50

As it maps the territory of the self, the essay details the particulars of everyday life, attuned, like Wordsworth and like Dutch genre painting, to the quite mundane and quotidian: taking a walk, mowing a field, observing a moth dying, contemplating a piece of chalk. The wonder is not that art can be made of such ordinary stuff, but that we should expect it to be found anywhere else.

G. Douglas Atkins, Tracing the Essay: Through Experience to Truth (2005), p.68

Essays are making a remarkable literary comeback ... [they] are being written out of the same imaginative spirit as fiction and poetry. And essays can rival the best fiction and poetry in artistic accomplishment. Why not? The essayist, too, can master imagery, character, symbol, metaphor, the ins and outs of narration.

Robert Atwan (series editor), The Best American Essays 1988, Ticknor & Field, New York: 1988, pp.ix-x

In light of the essay's transformations, today's poetry and fiction appear stagnant: the essay is now our most dynamic literary form.

Robert Atwan (series editor), The Best American Essays 1997, Houghton Mifflin, Boston: 1997, p.xi

Often one literary form dominates an era. In Shakespeare's time the play was the thing, and lyric poets and pamphleteers wrote for the stage when they turned aside from their primary work. A few decades ago, American novelists wrote novels when they could afford to but paid their bills by writing short stories for Collier's and the Saturday Evening Post. Today, novelists of similar eminence and ability — Joan Didion, Cynthia Ozick, Alice Walker, Jamaica Kincaid — become performers of the essay, for we live in the age of the essay.

Donald Hall (ed.), The Contemporary Essay, Bedford Books of St Martin, Boston: 1995, p.1

The essay induces skepticism. It is not altogether the fault of Montaigne. The essay is simply a watchful form, Hazlitt's thought is not shaken out like pepper on the page, nor does Lamb compose in blurts. Halfway between sermon and story, the essay interests itself in the narration of ideas — in their unfolding — and the conflict between philosophies or other points of view becomes a drama in its hands; systems are seen as plots and concepts as characters.

William Gass, Habitations of the Word, Cornell University Press, Ithaca: 1985, p.23

Entering the road laid down by tradition, the essayist is not content to pursue faithfully the prescribed itinerary. Instinctively, he (or she) swerves to explore the surrounding terrain, to track a stray detail or anomaly, even at the risk of wrong turns, dead ends, and charges of trespassing. From the standpoint of more 'responsible' travelers, the resulting path will look skewed and arbitrary. But if the essayist keeps faith with chance, moving with unmethodical method through the thicket of contemporary experience, some will find the path worth following awhile.

R. Lane Kauffmann, "The Skewed Path: Essaying as Unmethodical Method," in Alexander Butrym (ed.), Essays on the Essay: Redefining the Genre, University of Georgia Press, Athens GA: 1989, p.220

The essay writer is a chartered libertine and a law unto himself. A quick ear and eye, an ability to discern the infinite suggestiveness of common things, a brooding meditative spirit, are all the essayist requires to start business with.

Alexander Smith, Dreamthorp: A Book of Essays Written in the Country, Strahan & Co, London: 1863, p.25

In our century, when the grand philosophical systems seem to have collapsed under their own weight and authoritarian taint, the light-footed, free-wheeling essay suddenly steps forward as an attractive way to open up philosophical discourse ... The personal essay's suitability for experimental method and self-reflective process, its tolerance for the fragmentary and irresolution, make it uniquely appropriate to the present era, whether we want to label it late modernist or postmodernist.

Philip Lopate (ed.), The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present, Anchor/Doubleday, New York: 1994, pp.xliii & l

[The essay] is not part of any formal system whatever, adheres to the methodologies, the discovery procedures, the criteria for proof of no established discipline. In this way the essay is 'informal.' It steers away from logically or conventionally ordered sequences of elaboration, from introduction and conclusion, from the overly explicit transition; it obeys no compulsion to tie up what may look like loose ends, tolerates a fair amount of inconclusiveness and indeterminacy.

Lydia Fakundiny (ed.), The Art of the Essay, Houghton Mifflin, Boston: 1991, p.17

Current American creative nonfiction has buried the essay, its most interesting form, under a generic mountain of autobiographical narrative.

David Lazar, "Occasional Desire: On the Essay and the Memoir", in Lazar (ed.) Truth in Nonfiction, University of Iowa Press, Iowa City: 2008, p.111

The essay's precarious position between the non-fictional and the fictional also causes discomfort. Literary critics want to know where it 'fits' and are disturbed by the fact that it seems to stretch the fabric of definition at the seams.

Ruth-Ellen Boetcher Joeres & Elizabeth Mittman (eds.), The Politics of the Essay: Feminist Perspectives, Indiana University Press, Bloomington: 1993, p.12

The essay stands apart from both poetry and prose fiction, as well as from other forms of academic writing, in its emphasis upon the actual situation of the writer, and thus upon the personal nature, the 'situatedness', of all writing.

Kurt Spellmeyer, "A Common Ground: The Essay in the Academy", in Alexander J. Butrym (ed), Essays on the Essay: Redefining the Genre, University of Georgia Press, Athens GA: 1989, p. 255

Once generic distinctions start to leak, people bring in anything that might conceivably hold water. 'Literary nonfiction,' 'creative nonfiction,' and 'lyric essay' are some of the makeshift semantic hybrids in current use and designed to catch the sort of prose work which is very like an essay but which exploits the linguistic playfulness, associative logic, and imaginative license of poetry.

Arthur Salzman, Objects and Empathy, Mid-List Press, Minneapolis: 2001, p.viii

Unlike novelists and playwrights, who lurk behind the scenes while distracting our attention with the puppet show of imaginary characters - and unlike scholars and journalists, who quote the opinions of others and take cover behind the hedges of neutrality — the essayist has nowhere to hide.

Scott Russell Sanders, "The Singular First Person", in Alexander J. Butrym (ed), Essays on the Essay: Redefining the Genre, University of Georgia Press, Athens GA: 1989, p.31.

The essay has, then, the potential for being at least an inroad, if not indeed an attack, on monumental discourse because as a form it negotiates the split between public discourse — formal, ordered, impersonal, knowing, with pretensions to universality and fixity, and private utterance — tentative, personal, questing, provisional. If 'composition' is an edifice, the essay is a nomad's tent. It moves around.

Rebecca Blevins Faery, "On the Possibilities of the Essay: a Meditation", in Robert L. Root & Michael Steinberg (eds.), The Fourth Genre: Contemporary Writers of/on Creative Nonfiction, Longman, New York: 2002, pp.248/9

Every essay is the only one of its kind. There are no rules for making beginnings, or middles, or endings; it is a harder, more original discipline than that.

Lydia Fakundiny (ed.), The Art of the Essay, Houghton Mifflin, Boston: 1991, p.4

The overt etymological evidence, always triumphantly brandished at some point or other in studies on the essay, is a constant reminder of what we are all supposed to know and should under no circumstances be allowed to forget: that the word 'essay' comes from the French essai and essayer, to attempt, to experiment, to try out, and further back from the Latin exagium, 'weighing' an object or idea, examining it from various angles, but never exhaustively or systematically ... The essay is an essentially ambulatory and fragmentary prose form. Its direction and pace, the tracks it chooses to follow, can be changed at will ... The very word 'essay' disorientates the reader's horizon of expectations, for if it is associated with the authority and authenticity of someone who speaks in his or her own name, it also disclaims all responsibility with regard to what is after all only 'tried out' and which is therefore closer, in a sense, to the 'as if' of fiction. As with the idea that each essay is the only one of its kind, favouring the etymological definition quickly raises the question of whether the essay can be regarded as a genre at all, or whether it might not represent the very denial of genre.

Claire de Obaldia, The Essayistic Spirit: Literature, Modern Criticism and the Essay, Clarendon Press, Oxford: 1995, pp.2-3

Luck and Play are essential to the essay ... The essay shies away from the violence of dogma ... It thinks in fragments just as reality is fragmented and gains its unity only by moving through the fissures, rather than by smoothing them over ... the law of the innermost form of the essay is heresy.

T.W. Adorno, "The Essay as Form", tr. Bob Hullot-Kentor & Frederic Will, New German Critique, Vol.32 (1984), pp.152, 158, 164 & 171

A form of what we niggardly refer to as nonfiction, the essay traffics in fact and tells the truth, yet it seems to feel free to enliven, to shape, to embellish, to make use as necessary of elements of the imaginative and fictive — thus its inclusion in that rather unfortunate current designation 'creative nonfiction.' It is, we might say, a product of both nature and culture, whether or not the desperate term 'formless form' is quite deserved. Among the many dualisms that the essay inhabits, perhaps bridges, none is more important, I reckon, than that of literature/philosophy.

G. Douglas Atkins, Reading Essays: An Invitation, Georgia University Press, Athens GA: 2008, p.3

The essay is agnostic.

Rachel Blau Duplessis, "f-Words: An Essay on the Essay", in American Literature Vol.68 no.1 (1996), p.29

If you want to make money, don't write essays: write reviews or journalism; if, as more likely, you want advancement, again don't write essays: write academic articles. Genuinely informal writing requires as much skill and application as formal prose; to adopt a remark of Northrop Frye, the skill required for the essay is a special skill, like playing the piano, not the expression of a general attitude to life, like singing in the shower. Far from encouraging the Australian intelligentsia to develop this skill, a great deal seems set up to encourage it to do what it does best anyway, i.e. disappear up its own discursive formation.

Imre Salusinszky, in his Introduction to The Oxford Book of Australian Essays, Oxford University Press, Melbourne: 1997, p.4

As a literary form the essay has always had irresponsible boundaries.

Martin Gardner, in his Preface to Great Essays in Science, chosen and introduced by Martin Gardner, Oxford University Press, Oxford: 1997 (revised edition), p.xiv

Essayists are keen observers of the overlooked, the ignored, the seemingly unimportant. They can make the mundane resplendent with their meditative insights... The personal essay mimics the activity of a mind at work. It reflects discovery through writing... For me the magic of an essay is so often tied to its exploding of the commonplace, its deep investigation of something we tend to overlook or think entirely mundane and unworthy of our attention.

Patrick Madden, Quotidiana, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln: 2010, pp.4, 65 & 134

Montaigne endowed the personal essay with an intense commitment to tracking and tracing one's inner life - to a consciousness of consciousness that has been, perhaps, its more enduring and definitive quality.

Carl H. Klaus, The Made-Up Self: Impersonation in the Personal Essay, University of Iowa Press, Iowa City: 2010, p.18

Because essays, like most memoirs, are written and read by looking through the narrow keyhole of the letter 'I', essayists must always answer the 'So what?' question. Why should anyhow care that he had a rotten childhood, a love affair with turtles, or a glass eye? The wonder of the personal essay is how often readers do care. Most of us read essays for the same reason we read any story: to spend a little time in someone else's world. Even if this world is in a different time or place, or diverges from the particulars of readers' lives, the best essays ultimately arrive at someplace we all recognize — our struggles to love or feel at home with ourselves or find joy in what is extraordinary in otherwise ordinary things.

Bruce Ballenger, Crafting Truth: Short Studies in Creative Nonfiction, Longman/Pearson, Boston etc: 2011, p.23

The most striking and significant consensus can be seen in the tendency of essayists from every period and culture to define the essay by contrasting it with conventionalized and systematized forms of writing, such as rhetorical, scholarly, or journalistic discourse. In keeping with this contrast, they often invoke images and metaphors suggestive of the essay's naturalness, openness, or looseness as opposed to the methodical quality of conventional nonfiction. Likewise, they typically conceive of the essay as a mode of trying out ideas, of exploration rather than persuasion, of reflection rather than conviction.

Carl H. Klaus & Ned Stuckey-French (eds.), Essayists on the Essay: Montaigne to Our Time, Iowa University Press, Iowa City: 2012, pp.xv-xvi

The emergence of the essay at a time of tremendous civil, religious, scientific, and social upheaval suggests that new times demanded new discursive and narrative modes to cope with the changes... Montaigne rejects through the very practice of his essays, founded as they are on fragmented experience, the myth of truth, and looks to the lived experience and patterns among lived experiences.

Deborah N. Losse, Montaigne and Brief Narrative Form: Shaping the Essay, Palgrave Macmillan, London: 2013, pp.1 & 15

In its directness and intimacy, the essay is the ideal literary form for the twenty-first century. Overwhelmed by an endless flux of information, we inwardly crave the momentary stay against confusion promised by the essay... other traits commonly attributed to the genre include spontaneity and intimacy, stylishness, the exaltation of the fragmentary, the rejection of deductive logic, whimsicality, the avoidance of erudition, a dislike of dogmatism, an interest in neglected subjects, an idiosyncratic voice, playfulness, an emphasis on human fallibility, and a willingness to expose one's intellectual insecurities.

Jeff Porter, "From 'A History and Poetics of the Essay'", The Essay Review, vol.1 no.1 (2013), pp.8 & 15

I've always thought the famous idiom about the elephant — it's hard to define but you know one when you see one — was brilliant, except that it didn't apply to elephants. They are in fact extremely easy to define — big, grey, large trunk, etc. The idiom does apply, though, to the essay. Lots of people have tried to restrict it within the boundaries of a particular definition, but it never works. The only criterion, so far as I can tell, is quality, and even that's not a real criterion — a bad essay is still an essay. But, like the elephant, you certainly know a good one when you see one.

Harry Mount, writing in the Foreword to William Hazlitt Essay Prize 2013: The Winners, Notting Hill Editions, London: 2013, p.vii

Embracing tension, the essay lies between literature and philosophy, experience and meaning, fiction and fact, tradition and the individual, timelessness and time, a via media creature (which does not, contrary to appearance, equate with 'middle ground' or the moderate). The tension everywhere present in the essay, rooted in the here-and-now through which it works towards timelessness, which it comes to realize as inhering — incarnate — in the here-and-now, is crucial to an individual essay's success.

G. Douglas Atkins, "The Course of Interpretative Discovery: An Essay on the Essay, an Essay on Criticism", The Essay Review, Vol.1 no.2 (2014), p.8

When I say "essay," I mean short nonfiction prose with a meditative subject at its center and a tendency away from certitude... The essay... is a form for trying out the heretofore untried. Its spirit resists closed-ended, hierarchical thinking and encourages both writer and reader to postpone their verdict on life. It is an invitation to maintain the elasticity of mind and to get comfortable with the world's inherent ambivalence. And, most importantly, it is an imaginative rehearsal of what isn't but could be.

Christy Wampole, "The Essayification of Everything", May 26 2013, The Stone/New York Times

You and I have heard it many times — "essay" comes from a French verb meaning "to try" — followed by what's now almost a platitude: essays should be insightful, vulnerable attempts to understand the self in the world. But as I fall in love, haltingly, with essays, I need a new paradigm beyond trying. I consider myself an environmentalist, a pescatarian at times, and yet I'm drawn to the old phrase "to take the essay," which meant "to draw the knife along the belly of the deer, beginning at the brisket, to discover how fat he is" right after the animal has fallen dead during a hunt. (That's how James Orchard Halliwell-Phillips, a nineteenth-century Shakespearean scholar, defines it in his dictionary of archaic words.) Increasingly my ideal essay involves that kind of impromptu, exploratory surgery—in the dark, brambly woods of consciousness, we hunt for insights and unreliable memories until they are captured on the page; with the nicked, scratched blade of writerly attention, we cut through our conditioned perceptions, through the instep arch of our sleepwalking carbon culture, to see just what kind of substance is there, what was hidden beneath the chatter and propaganda; both reader and writer return to the village, so to speak, with blood stains because things got a little messy.

Gregg Wrenn, "On Writing for the Future, and Drawing the Knife along the Belly of the Deer", Monday May 18 2015, essaydaily.org

In a sense, almost all essays are about the essay, because essays are so hopelessly, or better yet, hopefully, self-reflexive. If essays are considerations, thought processes, meditations, whether critical, lyrical, dialectical, philosophical, personal, fragmented, epistolary, or manifested, they tend to betray self-consciousness of form.

David Lazar, "An Essay Upon Essays Upon Essays Upon Essays", in David Lazar (ed.), Essaying the Essay, Welcome Table Press, Gettysburg PA: 2014, p.1

A good essay seemed to question itself in a way that a novel or short story did not — or perhaps it was simply that the personal essay left its questions on the page, there for everyone to see; it was a forum for self-doubt, for an attempt whose outcome wasn't assured. … Cutting away what I consider the engine of the essay — doubt and the unknown, let's say — leaves us with articles and theses, facts and information, our side and their side, dreary optimism and even drearier pessimism, but nowhere to turn in a moment of true need.

Charles D'Ambrosio, Loitering: New & Collected Essays, Tin House Books, Portland, Oregon: 2015, pp 15 &.20

I've come to think that the genuine essay has certain persistent core features that have helped distinguish it over centuries, from its late sixteenth-century inception to its most recent post-modern examples. The essay has always been experimental, experiential, exploratory, and open-ended. It is hardly ever categorical, dogmatic, systematic, or conclusive. It resists narrow professionalism and academicism. In trying to summarize all of these features into a one sentence definition that embraces the essay's essential literary characteristics as I understand them, I would say, ideally: 'The essay, whether long or short, narrative, expository, or polemical, is a literary genre that enacts the processes and possibilities of thought and self-disclosure in a distinctive prose style'.

Robert Atwan, "Notes Towards the Definition of an Essay", River Teeth: A Journal of Nonfiction Narrative, Vol.14 no.1 (2012), p.117

Essays are barometers of the intellect. We are all atmospheric creatures, influenced by the cultural weather around us; the essayist takes it as her role to say something about the way the atmosphere plays upon a person and exerts pressure on the mind and its bearing. What causes the spirit to slump? What lifts it? The constant flux between lightness and heaviness is the basic biographical flux of human life. Essays gauge this flux but also respond to it by pressing back, meeting experience with an equal exertion.

Christy Wampole, The Other Serious: Essays for the New American Generation, HarperCollins, New York: 2015 pp 1-2

The essay, as it's often been described, is not a monumental form but rather something devious and loose, a provisional effort to bend reality's raw mess into meaningful shape.

Editor's Note, 2016 issue of The Essay Review

The essay, which in essence wants to wander, may pursue its adventure by the paradoxical means of an ordered stasis: all its elements arranged as if in a cabinet of curiosities, an elaborate microcosm that freezes in an image some version of the world outside the collection. In this essayistic Wunderkammer, things are allowed to be themselves alone, but will inevitably enter into metaphoric relations with each other, essaying lines of analogy or affinity.

Brian Dillon, Essayism, Fitzcarraldo Editions, London: 2017, p.126

“It is relatively easy to extract from the Essais moral maxims that can then be regrouped as thoughts. But such a practice runs counter to the form of the essay Montaigne invented. Let us not forget that Montaigne constantly plays with contradiction and always refuses to objectify and imprison his self in maxims or aphorisms. Far from depicting things, the author of the Essais is more interested in the passage of time over the different objects he writes about. The world acquires meaning only through the way the subject looks at it: a way that is always particular (and hence subjective) and situated in time and space. It is difficult to transform the Essais into a moralizing text.”

Phillipe Desan, Montaigne: a Life [tr. Steven Rendell & Lisa Neal], Princeton University Press, Princeton: 2017, pp.626-627

“A good essay is always on the move, always searching out links and currents of thought, because if it doesn’t it’s dead on arrival in the reader’s mind — a series of dull factoids, not ‘a contour map of consciousness’ or a Rough Guide to the essayist’s inner life.”

David Robinson, Books from Scotland, December 2018

“Will the essay as a mode of unconstrained expression survive? I’m growing sceptical, but I guess it all depends on how much future generations will prize free inquiry and open discussion.”

Robert Atwan, writing in the Foreword to Hilton Als (ed.), The Best American Essays 2018, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston & New York: 2018, p.xv

“The essay consists of double translation: memory translates experience; essay translates memory. … What personal essayists, as opposed to novelists or faux-naïf memoirists, do: keep looking at their own lives from different angles, keep trying to find new metaphors for the self and the self’s soul mates. The only serious journey, to me, is deeper into self. We’re all guaranteed, of course, never to fully know ourselves, which fails, somehow, to mitigate the urgency of the journey. … The work of essayists is vital precisely because it permits and encourages self-knowledge in a way that is less indirect than fiction, more open and speculative. One would like to think that the personal essay represents basic research on the self, in ways that are allied with science and philosophy.”

David Shields, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, Penguin, London: 2011, pp. 61, 152, 202

“The essayist’s job is to gather up the shards or map them where they are, to find the pattern out there or make one with words about the disconnections and mysteries. This reading of the world is a form of travel, questing and searching and gathering. Essays are restless literature, trying to find out how things fit together, how we can think about two things at once, how the personal and the public can inform each other, how two overtly dissimilar things share a secret kinship, how intuitive and scholarly knowledge can cook together, how discovery can be a deep pleasure…. [Essays] are a meeting ground, a place where the experiential and the categorical, the first-hand and the researched, converse, question, or just dance in each other’s arms for a while. Where the patterns and phenomena we thought we knew take on new meanings and depths or turn out to be strangers we are meeting for the first time.”

Rebecca Solnit, writing in her Introduction to Rebecca Solnit (ed.), The Best American Essays 2019, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston & New York: 2019, p.xvii

“Some of the essay’s often-cited elements include its extraordinary flexibility and mutability, its literary sparkle, its undogmatic, anti-methodical, anti-totalizing tendencies, its tropism toward ambivalence, doubt, scepticism, self-mockery, its freedom to wander and digress, its cockroach-like resilience and survival ability. All these are good things. I would just like to caution that we essayists not take too seriously our own defensive propaganda, or adopt too smugly this self-approving, narcissistic, idealizing portrait of the form. I who have championed the essay for so long am starting to grow impatient with these self-serving characterizations. Yes, essays can be charming, they have the appeal of the underdog. But let us not get carried away.”

Phillip Lopate, “My Love Affair with the Essay”, in Gail Low & Kirsty Gunn (ed.), Imagined Spaces, The Voyage Out Press, Dundee: 2020, p.173

“Given the various ways in which the essay bristles against academic writing — its resistance to introductions, to definitions, to generalization and abstraction, to accounts of origins, its freedom from discipline, rules, and criteria — it is no wonder that the field of critical work on the essay is sparse.”

Thomas Karshan & Kathryn Murphy (eds), On Essays: Montaigne to the Present, Oxford University Press, Oxford: 2020, pp.16-17. For Chris Arthur’s review of this volume, see the Spring 2021 issue of World Literature Today.

“When the century began, essays were considered box-office poison; editors would sometimes disguise collections of the stuff by packaging them as theme-driven memoirs. All that has changed: a generation of younger readers has embraced the essay form and made their favorite authors into bestsellers. We could speculate on the reasons for this growing popularity — the hunger for humane, authentic voices trying to get at least a partial grip on the truth in the face of so much political mendacity and information overload; the convenient, bite-sized nature of essays that require no excessive time-commitment; the rise of identity politics and its promotion of eloquent spokespersons. … The essay has always been an adaptable, plastic, shape-shifting form: it may take the form of meditation, reportage, blog, humor piece, eulogy, autobiographical slice, diatribe, list, collage, mosaic, lecture, or letter. Contemporary practitioners seem bent on further testing its limits.”

Phillip Lopate (ed.), The Contemporary American Essay, Anchor Books, New York: 2021, pp. xi-xii. For Chris Arthur’s review of this volume, see the January 2022 issue of World Literature Today.

“The essay’s position between subjectivity and objectivity represents the phenomenal character of the world and thus suggests an alternative to the model of truth as conceptual precision, abstracted from lived experience. Truth becomes the activity of subjects in the world rather than something independent of subjectivity or history.”

Erin Plunkett, “The Essay as Phenomenology,” in Mario Aquilina (ed.), The Essay at the Limits: Poetics, Politics and Form, Bloomsbury Academic, London: 2021, p.29.

“That the essay seems artless is one of its great ruses.”

Jeff Porter, “A History and Poetics of the Essay,” in Patricia Foster & Jeff Porter (ed), Understanding the Essay, Broadview Press, Peterborough, Ontario: 2012, p.xxiii

“If the function of the essay is to speak to moments of social and political crisis, to define aesthetic debates, and to reflect on the meaning of individual and collective identity, it is not surprising that the genre is as vital to the present as it has been to the past.”

Cheryl A. Wall, On Freedom and the Will to Adorn: The Art of the African American Essay, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill: 2018, p.217

“In its directness and intimacy, the essay is the ideal literary form for the twenty-first century. Overwhelmed by an endless flux of information, we inwardly crave the momentary stay against confusion promised by the essay. We relish, as Scott Russell Sanders wrote, ‘the spectacle of a single consciousness’ confronting the chaos of cultural overload to which we awake each day.”

Jeff Porter, “A History and Poetics of the Essay,” in Patricia Foster & Jeff Porter (ed), Understanding the Essay, Broadview Press, Peterborough, Ontario: 2012, p.ix [The quote is from Scott Russell Sanders’ essay “The Singular First Person,” in the Sewanee Review, 96 (1988), pp.658-672]

“Throughout history, essayists have conversed with each other through their pieces, in dialogues that might span decades or centuries. Montaigne quoted Seneca, Plutarch and Cicero; William Hazlitt wrote an appreciation of Montaigne; Virginia Woolf wrote about Hazlitt and Montaigne, and so on. The essay tradition has been a linked conversation, an invitation to form friendship with the reader and to affirm or joust with one’s fellow essayists.”

Phillip Lopate, “The Postwar American Essay, the Liberal Imagination and the Contemporary Essay,” in Mario Aquilina, Bob Cowser Jr, & Nicole B. Wallack (eds), The Edinburgh Companion to the Essay, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh: 2022, p.238. [For Chris Arthur’s review of this volume see the July 2023 issue of World Literature Today.]

“In order to count as political, the essay must intersect significantly with the concerns of the present moment; it must seek to affect an ongoing struggle. But in order to count as an essay — which is to say, deserve attention for its literary value — it needs to outlast the concerns of the present, or at least the terms in which the present has defined its concerns. Politics demands context; literariness is defined by the capacity to transcend context.”

Bruce Robbins, “Politics and the English Essay,” in Mario Aquilina, Bob Cowser Jr, & Nicole B. Wallack (eds), The Edinburgh Companion to the Essay, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh: 2022, p.226

“In a present that is hard to understand, we really need the context. Essayists situate the particular in the general and draw the relationships between them.”

Rebecca Solnit, “Contemporary Essayists in Focus,” in Mario Aquilina, Bob Cowser Jr, & Nicole B. Wallack (eds), The Edinburgh Companion to the Essay, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh: 2022, p.146

“That it is nonfiction might be the second-most agreed upon of our certitudes about the essay — right after the fact that we do not really have any.”

Jason Childs, “Essay, Fiction, Truth, Troth,” in in Mario Aquilina, Bob Cowser Jr, & Nicole B. Wallack (eds), The Edinburgh Companion to the Essay, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh: 2022, p.82

“What, after all, is an essay? What can an essay do or think or reveal or know that other literary forms cannot? What makes a piece of writing essayistic? Answers to questions about the essay frequently come in the form of negations, statements of what the essay isn’t: It’s neither poetry nor fiction; it may proceed by experimentation but it isn’t a scientific treatise and offers no proof; it deals with concepts and ideas but opposes what Georg Lukács calls the ‘icy perfection of philosophy’; it may tell the story of a self, but it isn’t autobiography or memoir; it may contain facts, but it’s certainly not always to be trusted. The essay invites readers down its many and winding paths but it isn’t so interested in providing a map.”

Kara Wittman & Evan Kindley (eds), The Cambridge Companion to the Essay, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 2023, (from the editors’ Introduction, p.1). [Chris Arthur’s review of The Cambridge Companion to the Essay is in the March-April 2023 issue of World Literature Today]

Francis Bacon (1561-1626), who pioneered the essay form in English.