Words of the Grey Wind

"[This is how Samuel Johnson] defined the essay: 'A loose sally of the mind; an irregular indigested piece; not a regular or ordered composition.' There are, it's true, plenty of essayists who write like that. Newspapers and magazines are full of them — pieces of zeitgeisty froth that evaporate on reading. But as a definition of what Chris Arthur is trying to do when he tries to make sense of the world, it's wrong on every count. ... [His essays] start in detail ... then wander with both wonder and gravid precision of language towards meditations on impermanence."

David Robinson, The Scotsman, 26 Sep 2009 (in full below)

This volume of new and selected essays is published by Belfast's Blackstaff Press. It draws on Irish Nocturnes, Irish Willow and Irish Haiku and presents some of their essays alongside three new pieces of work.

The book includes the haunting essay "Mistletoe", an early version of which was published in the Southern Humanities Review. The opening section is given below.

The cover illustration for Words of the Grey Wind is Michael Benington's painting "Eiders in a Gale". Chris Arthur comments: "The aptness of a Benington cover should be evident from the fact that one of the people to whom the book is dedicated is Arnold Benington. Michael is his son. Arnold Benington taught me how to dissect owl pellets and kindled my fascination for kingfishers, waxwings and other birds. He was a valued teacher and friend. That Edward Armstrong, author of Birds of the Grey Wind — the book that inspired my title — was related to the Beningtons adds another pleasing loop of unexpected connection."

The Foreword to Words of the Grey Wind is by eminent scholar and literary critic John Wilson Foster. This is what he says about the book:

Foreword

By John Wilson Foster

Most of the essays in this splendid book have been chosen from three volumes originally published in Colorado: Irish Nocturnes (1999), Irish Willow (2002) and Irish Haiku (2005). In hindsight, there was something fitting about the quiet first appearance of these volumes in the American West — quiet in their pleasingly fine format (with their delicately suggestive titles) as well as in their unassuming arrival from an unsuspected source, a hitherto unknown Irish essayist. For like the essays themselves, the unassumingness was rather deceptive. The beginning may have been modest but since over thirty essays were collected in just three years, there was an impression of cumulating work having kept itself in reserve and the pressure of its contents under rein. (The inclusion of three new essays in Words of the Grey Wind is a welcome suggestion that the writer is now in mid-flow.) Moreover, just as the essays typically begin without fanfare or flourish, with what may even appear as casualness or arbitrariness, and then unfold themselves resolutely if elegantly, so this published selection signals an important stage in what I believe will be the widening spiral of Chris Arthur's reputation beyond discriminating readers of choice books published by a Colorado publisher and into the more robust British and Irish literary scene.

My own first acquaintance with Arthur's writings was accompanied by a trivial coincidence of the kind the author might himself have enjoyed and that added a personal note to the otherwise impersonal swim of a deeply impressive writer into this reader's ken. I was several pages into an offprint of Arthur's essay, 'Miracles' when its inspiring figure of Brother Erskine gradually lifted itself off the page and into sharp recognition, much like a photograph materialising in the developing tray. He became D.B. Erskine, one of the masters who in grammar school had quickened my love of literature. I thought that the essayist who had brought him back to life was an ex-schoolfellow of mine; I was wrong, but my acquaintance with a characteristically thoughtful essay led to my acquaintance with its author.

David Erskine, I learned, had left my Belfast grammar school, taken the cloth, and become chaplain at the college where Arthur was a pupil. Arthur, with his attraction to beginnings and unfoldings, might enjoy someone else's memories of Brother Erskine's pre-clerical career (a bare decade after the end of the Second World War) when this physically imposing, Clark Gableishly handsome ex-tank commander embodied the worldly-wise. I see him striding down our interminable corridors with an improbable number of books tucked under his impressive wingspan, with his gown flapping as if for flight. I see him perched precariously on a chairback (as Arthur does too) reading Arthur Conan Doyle to us in a sonorous voice, all the while smoothing an invisible moustache, perhaps in gestural memory of a suitable wartime adornment. (When some boy's books clattered off the desk, D.B. Erskine would mix his world wars and cry, 'Someone dropped a Mills bomb!') I see him, too, on dining hall duty, silencing a turmoil of working-class schoolboys with the clangs of a huge handbell and the bellowed observations — 'Bedlam! Chaos! Pandemonium!' Arthur's Brother Erskine, to which I leave the reader of this wonderful essay, is a figure unfolded in a new direction, one doing characteristically fertile philosophic duty, and my own memories merely add a caption to Arthur's chart, in this essay and elsewhere, of all our movements through time and space with their accompanying alterations in our opinions, in our bodies, and finally in our claims to identity and existence.

The movement of Arthur's mind is one of exfoliation. His modus operandi, which after a few essays the reader begins with pleasure to anticipate, is a measured departure from a particular object, incident, word or memory, often commonplace but sometimes highly personal and sometimes intrinsically poetic — ferrule, table, mistletoe, swan's wing, one afternoon's occurrence — into its ramifying implications, symbolisms and meanings. An extended metaphor is often the required ignition. The pursuit of the subject is a 'long foray', to borrow an oxymoron from Seamus Heaney, and exemplifies not only the parsings, propositions and interrogations of analytic thought, but also its reservations, denials and reassertions, until, oddly, the essay's stages of argument seem to exist simultaneously, even though points along the way have been decisively made and conclusions reached. The alertly cognitive becomes something akin to reverie without loss of alertness or cognition. He may have used the term 'nocturne' for one of his titles, but 'fugue' seems closer to the development of an Arthur essay. The net result is metaphysical: Arthur's acute inquiry is accompanied all the while by an awareness that nothing, be it argument or the stuff of the world, comes to final rest.

I say 'net' advisedly, since 'tendril' in the suggestive sense of relentless reticulate growth is one of Arthur's favourite words and characterises his own procedure as much as the world and his experience of it that he chooses to ravel and unravel for us. In Arthur's world, everything is connected in shrinking degrees of separation. To display the restlessness of matter, Arthur typically tracks the things and thoughts of the world to their far reaches where they, like all transient particular existence, are dwarfed and contemplation itself is spent, the essay completed. When he speaks of 'the smoke of forms' that blows across each place over time and of 'the endless tundra of extinction', I am reminded of H.G. Wells' Time Traveller courageously taking his machine not to the ends but the end of the earth because he must see his scientific pilgrimage through. (The writing desk is Arthur's time machine.) This cosmic awareness of endless material motion has its dark aspect as though Arthur's essays were long and eloquent disappointments, with (at times) Larkinesque or even Beckettian accents. 'Swan Song', in which he contemplates his stillborn son, is unswervingly frank and to think this deeply sad event into its farthest implications, beyond fatherly grief and human loss, is an extraordinary feat.

The binaries we wrestle with, and usually shrink from, surface and submerge in these essays with an unfashionable candour: the metaphysical and the mundane, the commonplace and the miraculous, the physical and the spiritual, the accidental and the destined, the personal and the universal, the temporal and the eternal. Time and again the essayist seeks to resolve these oppositions as tie-breaks in the realm of some invisible other province. At the heart of the essays is a paradox: transcending of the self is sought through a relentless examination of the life. Heaney's word 'squarings' comes to mind when I think of the task of squaring or reconciling opposites in each Arthur essay, a task self-imposed from the outset but given all the appearance of a necessity freshly unfurling as the essay proceeds. Biology (especially Darwinism) helps, so too do physics, chemistry and astronomy. And a vestigial Christianity. Arthur shares his reading with us along the way, and from his essays I've taken note of fascinating-sounding studies I intend to read. But above all, Buddhism helps. Presumably as a result of his study and practice of Buddhism, his essays are courteous yet firm assaults on the Ineffable, part of a book long, probably lifelong campaign to come to rest in some Truth where the commonplace and the epiphanic conjoin, because the miraculous can only exist in 'the stupendous fabric of the real'. There are some admissions of defeat in the essays, but even when Arthur's campaign loses heart or self-justification (if 'everything is ineffable', then why seek to know it?), it is still a worthwhile and courageous one.

Arthur's Northern Irishness has been part of the fabric of his reality: his quiet Belfast upbringing and schooling and the later, if indirect, impact of the so-called 'Troubles'. The latter were, in actuality, a disgraceful thirty-year record of cruelty, of violent rebellion, reprisal and counter-insurgency. In a writer much concerned with transcending the coordinates of time and place, it was a subdued coincidental pleasure to find a timely set of rhetorical but morally urgent post-Troubles questions in 'Witness': 'I often wonder what ought to be remembered from Ulster's years of agony and turmoil... should we recall the dates of dreadful crimes and what was done, the names of individuals slaughtered and those who did the slaughtering? Or would it be better to let a slow tide of forgetfulness accumulate and slowly buoy us toward healing, forgiveness and reconciliation?' We might be tempted to add one more Arthurian question: how does one square the requirements of morality with awareness of the inevitable extinction even of morality?

Ireland, of course, has produced its quota of essayists, from Oliver Goldsmith through (among others) Thomas Davis, Robert Lynd, Thomas Kettle, Stephen Gwynn and Filson Young to Hubert Butler. But if Lynd can be regarded as the Irish exponent par excellence of the English essay, it's clear that Arthur belongs to some other tradition, if he is not sui generis. His thought-processes are too unconfined, his subjects at once too spacious and narrowly focused, his procedure too conceptually chaste, and his intention too severely tasking, for the English essay. His writing has some of the curiosity of Ciaran Carson's prose books, with their lodes of charming arcana, but does not have Carson's almost metaphysical wit. One thinks instead of Octavio Paz or Gaston Bachelard, at times of a soberer and longer-winded Borges. But this is trawling the academic net, as Seamus Heaney once remarked of such critical activity. If an Irish affinity must be sought, then the poetry of Michael Longley, with its finely-spun lyrical procedures, moral presence and its almost Eastern sensibility, comes to mind. In any case, Arthur's essays reveal a rarefied and rare, if not unique intelligence, and this selection from Blackstaff Press is a cause for congratulation and celebration.

John Wilson Foster is Professor Emeritus of English at the University of British Columbia. Born and raised in Belfast, he holds a BA and MA from Queen's University and a PhD from the University of Oregon. In 1986-87 he was Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Irish Studies (Belfast). He was Leverhulme Visiting Professor at the University of Ulster's Academy for Irish Cultural Heritages in 2004-5, Armstrong Visiting Professor at St Michael's College, University of Toronto, in 2006. Among his many publications are Irish Novels 1890-1940: New Bearings in Culture and Fiction (2008); The Cambridge Companion to the Irish Novel (2006); The Age of Titanic: Cross Currents in Anglo-American Culture (2002); Recoveries: Neglected Episodes in Irish Cultural History (2002); The Titanic Complex: A Cultural Manifest (1997); The Achievement of Seamus Heaney (1995); Colonial Consequences: Essays in Irish Literature and Culture (1991). He is Senior Editor of Nature in Ireland: A Scientific and Cultural History (1997). He recently returned to Ireland from Canada and is a visiting senior research fellow at Queen's University, Belfast and resident in Portaferry, Co. Down.

From "Mistletoe"

If — impossibly — she was swinging there now, part of the view would seem unchanged. On her right, the familiar redbrick of the house. A tall hawthorn hedge, neatly clipped, still standing to her left. Ahead, the same copper beech tree that has grown in that spot for almost a century now. But this would give the first indication of difference, for the copper beech she used to see from her swing was only eight feet high. Now it's close to eighty. If she turned round she'd see the plum trees she ate fruit from every summer of her childhood, always careful to avoid the wasps that burrowed their way into the ripest plums, devouring them from inside, a buzzing, easily provoked core, writhing black and yellow around the stone. The plum trees are more gnarled, a little bigger, but still recognizably the same. Slow growers anyway and regularly pruned, they don't display the copper beech's dramatic index of time's passing.

Despite some seeming constants, though, almost everything has changed. The house she knew as home is now inhabited by strangers. On the other side of the hawthorn hedge, the wildflower-strewn field — where she and her sisters often played — has disappeared beneath the tar and concrete of a housing estate. Beyond the copper beech, just out of sight of the swing, the five mature chestnut trees she knew so well have all been felled. Almost continuous traffic now roars past on the quiet road they once shaded. Seventy years have passed since my mother sat on her swing in this secluded Irish garden, her firm, fifteen-year-old muscles pulling on the ropes. Her then unmet husband is now already dead ten years; her unborn sons have grown children of their own.

When I think of that moment now, the image that comes most forcefully to mind is of an empty swing. It's still gently in motion, suggesting that we've just missed someone, that they stepped out of the picture only moments ago. The scene is still suffused with a strong sense of their being there — like putting your hand on a rumpled bed and finding a patch still warm from where someone has been sleeping. Though strong, this sense of presence is illusory. The swing has long gone. The apple tree it hung from was cut down years ago. Almost a life-time has passed from when my mother sat there as a girl, confidently swinging into womanhood. Her muscles are now frail and wasted. The energetic arcs as she pulled herself high on the swing are a world away from the old woman who can't pull herself out of a chair unaided. Had the swinging girl been able to see her future self, she would have been shocked and disbelieving. Looking back, my mother laments her loss of youth and raw, animal vitality. She has reached the nadir of life's swing. Movement that was once so fluid, so easy, has become slow, laboured, filled with pain and discomfort. Now "decrepit" is the word my mother chooses to describe herself. She pronounces it with angry disgust and a ghost of the surprise her earlier self would have felt had she been able to glimpse the future; it's as if she still can't quite believe how age and infirmity have overtaken her.

Despite her decrepitude, though, the seed she sows by telling me about this vanished time has taken vigorous root in my imagination. Looking back, I can see her dappled with light as the sunshine falls upon her through the leaves. The weight of her body, and the backwards and forwards motion of the swing, send tremors through the tree that shake loose some apple blossom. The petals fall on her dark hair like prophetic snowflakes, studding it with the white it will one day turn. The sun is always shining in this limbo-land of the imagined past. A voice has just sounded there, calling my mother inside for tea. The grassy path leading to the house shows soft indentations caused by her light tread. Released from the lithe pressure of her youthful body's running weight, the blades are slowly bending back to their original position. Soon the hypnotic pendulum of the empty swing will stop. The same iron laws that command bent grass blades back to upright rule that its motion must slow and return to stillness.

Reviews

"Just because we're celebrating the tercentenary of Samuel Johnson's birth this year, we shouldn't automatically assume that he got everything right in his great dictionary. This, for example, is how he defined the essay: 'A loose sally of the mind; an irregular indigested piece; not a regular or ordered composition.' There are, it's true, plenty of essayists who write like that. Newspapers and magazines are full of them — pieces of zeitgeisty froth that evaporate on reading. But as a definition of what Chris Arthur is trying to do when he tries to make sense of the world, it's wrong on every count. Don't worry if you haven't heard of Arthur. Unless you have somehow managed to lay your hands on three collections of essays — Irish Nocturnes, Irish Willow and Irish Haiku — published obscurely in Colorado over the last decade, you won't have done. Now that he's finally published on this side of the Atlantic, however, you have no excuse. Words of the Grey Wind (Blackstaff Press, £12.99), incorporates three essays from each of those volumes and includes three new ones. They start in detail — a piece of linen, the sound of his father's walking stick, a fossilised whalebone, an empty room, memories of the sounds of trains — then wander with both wonder and gravid precision of language towards meditations on impermanence. I'll give just one example (wildly oversimplified, but you can get the gist). 'Miracles' opens with Arthur contemplating a fossilised whale's earbone. Otoliths are milky white stones the size of a small pea in fish, crystalline grains of carbonate of lime in humans: either way they grow apparently out of nothing, accreting density over the course of life, always with the evolutionary aim of providing balance. The 32 million-year gap in time and space between fossil and the hand holding it might seem to hint at the miraculous. It doesn't — these are just co-ordinates on the passage to extinction. So he thinks about his own death, and how one day he might be buried holding the fossil. It wouldn't be a symbol of hope. 'Rather it would act as a full stop and anchor, celebrating at journey's end, as I will be dumb to, the sacred, the miraculous ... looped indelibly, intriguingly in hard concentric circles, into the invisible otoliths that there are at the heart of each seemingly ordinary moment.'"

David Robinson, The Scotsman, 26 Sep 2009

"Arthur's sensibility is at once lyrical, moral and humane... The formal procedures of [his] thought — the shift from the micro to the macro view, the shift between the personal and the universal — give these essays great scope... [T]his is a very welcome volume which contains... memorable essays of great poise and grace."

Ross Moore, writing on the Cuture Northern Ireland website

"Two years ago, I reviewed Chris Arthur's Irish Haiku for an academic journal, and fell in love with a very superior essayist. This current volume is a selected collection, containing some of the same essays (which were a joy to re-read) and some ones that are new, or new to me. Arthur's is an uncommonly probing mind, one given to meditation. [It] pivots gently around words and their associations, but always corrals the apparently errant thoughts into an elegant whole. He has an eye for the emotional depth-charges that take one deeply into experiences of family, place and event ... What Arthur ... seeks to do is to find (or is it create?) the epiphanic moment, the moment that reveals significance, that marks events as meaningful beyond their mundaneness. Little things — bones, ferrules, pieces of linen — can flesh out character, changes in lifestyle, major historical shifts, and give rise to speculations on the big questions of life and mortality, and raise questions about the sacred and religion ... Arthur's is a well-stocked mind and his journeyings are full of electrical frissons, and gifts garnered along the winding paths. He may take his bearings from Ulster, and derive his sense of self and family from there, but he also moves confidently among the great religions of the world, and the minor ones too, and treats them with reverence if they enrich his understandings. We move in heady arcs from Leakey's discovery of hominid footsteps in Tanzania, to the Buddha, to Norse Eddas, and Sir James Frazer, Virgil and back to a garden swing in Ulster in 1932, when in Arthur's company we hear about mistletoe ... For literary readers, Arthur's love affair with language is infectious ... [his] prose is meditative magic."

Frances Devlin-Glass, "Epiphanies in Ulster", review of Words of the Grey Wind in Tinteán No.19 (December 2009), p. 26.

"Despite all the tradition of extraordinary essayists — from Montaigne to Adorno, from Bacon to Borges and Camus, from Baudelaire to Cotzee, from Shelley to Yourcenar, from Emerson to Epstein, from Shaw to Sontag — the status of the essay form is still questioned and, alas, essays, or 'creative non-fiction', are often taken only as a minor literary expression ... Hopefully the release of this new book may lead critics and readers to the discovery of Arthur's exceptional talent as an essayist ... Chris Arthur is a consummate philosopher ... who draws freely from religion, philosophy, biology, physics, astronomy, chemistry and history ... His mastery regarding the literary complexities of the essay form surfaces in his intelligent and perceptive use of sources that are, at the same time, varied and deep; Arthur knows how to balance depth and fluidity in the text, and this makes the quality of his essays. Taking memories, unique incidents or particular objects to start his essays, Arthur proceeds in his poetic desquamating process; throughout the book this process, often transmuting the mundane into the sacred, is also reinforced by the use of a keen analytical thought and of a very poetical language, thus transforming seemingly common things — from a ferrule to a cup of tea — into experiences charged with symbolism and philosophical content."

Luci Collin Lavalle, review of Words of the Grey Wind in Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies, No.11 (2009), pp.225-228.

"Arthur's short introduction, 'The Infinite Suggestiveness of Common Things', is itself a guide to the contemplative manner and content of the thirteen essays that follow ... Family recollections frequently provide the 'pinhole of the familiar' from which Arthur begins to reflect ... Often it is a particular object — an animal bone, a ferrule, a fossil — that sets the reflection off, and Arthur writes with tender eloquence of such things: 'To cup a bullfinch's bones in your hand, to feel their almost nothingness and to know that woven into this desolate remnant was the brilliant colour of the plumage, the notes of a particular song, the shape and patterning of the eggs, a whole life-cycle and history stretching right back to the dinosaurs, is to wonder at the terrible intricacies, the beauty and savage violence of life's designs.' These are the patterns and designs that Arthur endeavours to outline and explore, while the enterprise expands to questions of origin, faith and meaning ... There is wondering but no insistence here."

David Burleigh, Journal of Irish Studies, Vol XXV (2010), pp.60-62.

“After happening upon 1989’s Best American Essays anthology, Chris Arthur turned to writing his own essays, which labor he’s been faithfully pursuing for the past two decades, unassumingly publishing in dozens of literary journals and four books. This collection includes his greatest hits, 13 glowingly lovely essays, incisive explorations of everyday things, carrying on the spirit of Montaigne. ‘Is it not reasonable to claim that there are miracles woven into every moment?’ Arthur asks, then proves again and again that it is.”

Patrick Madden, Fourth Genre: Explorations in Nonfiction, Vol.12 no.2 (2010), pp.187-189.

"In Arthur's accomplished hands, the essay becomes a mosaic of meditation, simultaneously illuminated by the singular light of an examined moment and the zodiacal light of time's broad ecliptic."

Elizabeth Dodd, review of Words of the Grey Wind and Irish Elegies, Southern Humanities Review, Vol.45 no.1 (2011), pp.103-107. The full review may be read here (167 KB PDF).

"Arthur is, by now, one of the most accomplished essay writers in Irish letters of the past three decades. His work may be trained on the personal and the past, but its messages are never confined to these coordinates. In his 'Foreword' to Words of the Grey Wind, John Wilson Foster succinctly conveys the orientation of Arthur's work: 'At the heart of the essays is a paradox: transcending the self is sought through a relentless examination of the life' (xiv). Arthur's essays, then, aggregate the numinous and the everyday in explorations of the sources of the 'self'. His vision may often be held by that which has been and gone, but which may have left barely perceptible watermarks on the minds of those who experienced its energies. Yet the past is always an implicit reminder of the transience of the present and of the future — just as we imagine the past, we imagine our way into the future. If our versions of the past are contingent and skewed, then our present is founded on uncertainty and chance. But none of this depresses the value of life in Arthur's essayistic meditations, it merely reinforces his ecological inclination to view life, all life on earth, with humility and awe."

Eóin Flannery, 'So many destinations in one place': Chris Arthur's Words of the Grey Wind: Family and Epiphany in Ulster and Irish Elegies, a review article in Irish Studies Review, Vol.19 no.4 (2011), pp.433-436.

"Because his essays, like all essays, never quite resolve into a kernel of wisdom, never quite put a subject to rest, you'll find Arthur returning across different pieces to some of the same ideas, such as the value of paying attention to the quotidian, or the interconnectedness of all things, or the improbabilities of existence; but with each recursion, the language is fresh, as is the occasion that gave rise to the new meditation, so that in Chris Arthur we find a guide to the contemplative life. Reading his essays, we afford ourselves the time for sustained engagement with a subject."

Patrick Madden, "Is Chris Arthur Making Us Smarter?" (63KB PDF), Fourth Genre, Vol.14 no.1 (2012), pp.207-211

“The collection opens with ‘Kingfishers’, weaving almost all the book's themes into its first 18 pages. A masterpiece of linked juxtapositions, the narrative shifts from nature, to memory, tragedy — insanity even — and slowly back to the bird, its and our transience in the scheme of things. That description is inadequate to the richness of the writing, for like in so many of these essays, ‘Kingfishers’ spins question on question, picking away at, if not entirely unravelling, the Gordian knot of what it is to be human …. Many of Arthur's essays take an object or event — the ferrule on his father's cane, a conversation in a bookshop, the fossilised bone of a whale — from which he crafts reflections on the myriad of connections which lead to where we are and what we will become. There are frequent references to Ulster and his family roots, but my sense is that these are staging for his main concerns — this is not so much a book about place, as 'our place in the world' … Words of the Grey Wind achieves that rare feat of being both deeply personal and yet universal in message. It's evident that Arthur has studied philosophy and theology, and there's a recurring influence of Buddhist teachings in any of the pieces. But mostly, there's an existential underscore to his voice — a sense of being alone in the enormity of it all — that resonates with me and is perhaps why I liked this collection so much.”

Mark Charlton, “Shopping My Library — Words of the Grey Wind”, Views From the Bikeshed, Wednesday, July 31 2019.

Words of the Grey Wind can be bought from:

"Essays draw a language-map so dense and free you can find yourself on it — and lose yourself in it — positionality lost and found."

Rachel Blau DuPlessis

Contents

- Foreword

by John Wilson Foster - Introduction: The Infinite Suggestiveness of Common Things

- Kingfishers

- Ferrule

- Meditation on the Pelvis of an Unknown Animal

- Linen

- A Tinchel Round My Father

- Table Manners

- Swan Song

- Train Sounds

- Witness

- Miracles

- Mistletoe

- Room Empty

- Waxwings

Mistletoe (Viscum album).

The baby who became the girl on the swing in "Mistletoe".

The convex mirror referred to in "Room, Empty," one of the new essays included in Words of the Grey Wind.

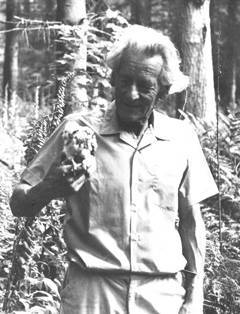

A formative influence in Chris Arthur's youth, Arnold Benington taught biology at Friends' School Lisburn, helped found the Copeland Island Bird Observatory, and contributed articles to the Irish Naturalists' Journal and other publications. He's pictured here with a sparrow-hawk chick in a forest near Hillsborough, County Down.

A sparrow-hawk chick in the nest with three unhatched eggs. Birds are an important touchstone in many of Arthur's essays — with kingfishers, blackbirds, swans, waxwings, corncrakes, owls etc often carrying considerable metaphorical cargo. In Irish Willow, "Transplantations" makes specific use of the image of a sparrow-hawk's nest.

The kingfisher (Alcedo atthis). Sightings of this bird are used to pace and punctuate "Kingfishers", one of the most effective essays in Arthur's oeuvre. This image is taken from Naumann's Naturgeschichte der Vögel Mitteleuropas (Natural history of the birds of central Europe).

Bohemian Waxwing (Bombycilla garrulus). The sighting of a small flock of these rare winter visitors to Ireland becomes the key point of focus for "Waxwings", a wide-ranging meditation on memory.

The Scottish poet and essayist Alexander Smith (1829-1867) provides the title for the Introduction to Words of the Grey Wind. In Dreamthorp: A Book of Essays Written in the Country (1863), Smith suggests that the essay-writer has "an ability to discern the infinite suggestiveness of common things".