Hidden Cargoes

"If anyone can lure out of hiding the mysterious secrets of the things of this world, and turn the familiar unfamiliar, the everyday magical, it's Chris Arthur. One of our greatest living essayists, he brings a rare combination of tenderness, power, care and, at times, ghoulish humor to the page."

Phillip Lopate

The electricity of wonder runs through everything, no matter how often we fail to notice it. Hidden Cargoes tries to make that electricity more evident by highlighting the extraordinary nature of ordinary things and experiences. In this collection, Chris Arthur ranges over subjects as various as a girl’s ear, a vulture’s egg, the letters in a Scrabble game, a sprig of witch-hazel, and the chasms of complexity contained in an ordinary moment. Whether he’s writing about such things, or looking at owls, leaves, a street in his hometown, the symbiotic interrelationships in the stomach of a termite, a souvenir cigarette box from a ship sunk in World War II, or the coincidence of three hearts beating simultaneously together, what gives these unorthodox meditations their appeal is the way in which — with striking lyricism — they tap into unexpected seams of meaning-mystery in our everyday terrain. Poet Mary Oliver’s assertion, “To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work,” has been chosen as the book’s epigraph. The constituent essays in Hidden Cargoes offer twelve idiosyncratic exercises in paying attention.

Hidden Cargoes was nominated as one of the California Review of Books’ Ten Best Books of 2022. It was also shortlisted for the 2023 Rubery Book Award.

This is how the book begins:

William Blake’s famous lines urge us

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.

This book challenges those who dismiss Blake as a dreamer or a madman. For them, sand grains are just sand grains, wildflowers no more than simple blooms. They believe that our hands can enclose nothing greater than what fits neatly in our grip, and that an hour is always confined within the palisade of its temporal duration. I leave to visionary geniuses like Blake the task of seeing on a scale that reveals worlds, heavens, infinity and eternity. My aim is more modest. My essays try to strip routine’s dulling insulation from the wires of experience so that the voltage of what’s there can touch us, make us aware of the hidden cargoes that are held in such abundance in the unlikeliest of places — a girl’s ear, a cigarette box, the letters of the alphabet, an owl’s skull, a sprig of witch-hazel. However much we contrive not to notice it, the electricity of wonder runs through everything. The twelve exercises in paying attention that constitute this book try to make that electricity more evident.

At the start of Portrait Inside My Head, Phillip Lopate provides an Introduction that’s sub-titled “In Defense of the Miscellaneous Essay Collection.” Since Hidden Cargoes is such a collection, should I likewise start by defending it?

Perhaps.

But such a tactic risks undermining what it’s meant to support. Faced with an opening salvo of authorial defense, readers may suspect that what they’re about to embark on lacks legitimacy. Why would it need to be defended unless its status was dubious?

I can see why almost any book might be thought to require an opening apologia. In a world in which so many people live in terrible need, the time and resources claimed by writing and reading might be thought questionable — frivolous, uncaring, selfish, irrelevant — unless a link can be demonstrated between them and some practical remedial upshot, a contribution to the common good. That apart, I see no reason why a collection of essays needs any more justification than a novel or a play or a book of poems.

In an essay about essays, provocatively entitled “In Defense of Incoherence,” E.J. Levy writes that “the form doesn’t lend itself to mass market sales.” But, she says, “that is precisely its charm and our pleasure in reading it.” In her view, part of the appeal of this genre lies in the fact that it provides a “respite from the clamor of commerce.” In putting together collections, she urges essayists not to succumb to the pressure of making their work more palatable to the economic exigencies of publishing, particularly by presenting it in a way that obscures the individual independence of each piece. To give the impression that essays can be subsumed beneath some organizing principle, to pretend there’s an overarching structure according to whose linear blueprint they unfold, is to betray their essential nature. “The first impulse that brought us to the essay form,” Levy reminds us, is art. And art is “not about the market or clever formal conceits, or even publication, but about wonder.”

I hope what I’ve said doesn’t swim against the current of Levy’s argument. The idea of paying attention and, by so doing, seeing the hidden cargoes carried in the things around us, offers a loose commonality that links the essays I’ve assembled. But I wouldn’t like it to be taken as a sign that I’ve surrendered to any kind of organizing principle. I join Levy in condemning such devices. The book’s title and epigraph, and what I’ve said in this Introduction, provide only the most general orientation. I’ve no desire to disguise the essentially miscellaneous nature of Hidden Cargoes. To invent some organizing principle that forces things into line, that gives the impression of a single narrative running unbroken from beginning to end, would be dishonest. The pages that follow don’t dance to this tune. The essays are independently intelligible and can be read in any order — though I’ve tried to arrange them in a way that’s in harmony with the music of their unfolding.

Some readers find this kind of collection an alarming prospect. They’re suspicious of the absence of a point-by-point progression. They feel uneasy outside the safe anchorage provided by linearity, where everything conforms to a predictable pattern of unfolding. If such readers haven’t fled the scene already, let me offer three reassuring touchstones — without, I hope, introducing the artificiality of the kind of organizing principle that Levy rightly condemns, or mounting a preemptive defense that might simply undermine what it seeks to foster.

First, as Graham Good puts it, “At heart, the essay is the voice of the individual.” To the extent that an individual’s voice reflects one particular personality, history, and worldview, Hidden Cargoes can claim that degree of homogeneity. Secondly, I agree with Levy about the fundamental nature of art. All of my essays share a common origin. They are rooted in moments of wonder. Thirdly, in a comment that nicely catches the way in which single essays relate to a collection, Richard Chadbourne suggests that the essay “is both fragmentary and complete in itself, capable both of standing on its own and of forming a kind of ‘higher organism’ when assembled with other essays by its author.” Hidden Cargoes is precisely such a beast. All of its constituent body parts contribute to what the “higher organism” is concerned with — namely exploring the extraordinary nature of the ordinary.

Reviews

“Belfast born Chris Arthur is not only the most accomplished Irish essayist working at present, he also stands among the finest practitioners of the form in the Anglophone world. A multi-award-winning non-fiction writer, he has been described by Phillip Lopate as ‘one of our greatest living essayists’ and by Robert Atwan as ‘among the very best essayists in the English language today’. His latest collection, Hidden Cargoes, will further cement that deserved reputation… Although the twelve essays here are not connected in their subject matter — they range from the inside of a termite’s stomach to the shape of a girl’s ear — they are connected in their method. Part of the joy, then, of reading Arthur is that the reader comes to expect an entire universe of meanings to unfold out of the skull of an owl or even something as commonplace as a leaf that has blown onto a driveway.”

Eoghan Smith, “Unspooling the immense chain of being,” review of Hidden Cargoes in Books Ireland, December 2022

“Hidden Cargoes — like Chris Arthur’s previous eight essay collections — is a book that can change your life, not so much your behaviors and beliefs but how you relate to the world around you. That is, to the objects in the room in which you read his pages and to all you encounter as you observe what passes through your immediate perceptions … Normally, as Arthur notes, we take so much for granted that the familiar dulls our perceptions: ‘It breeds a kind of existential drowsiness, so that we pass our days giving scant attention to what’s real.’ Arthur’s goal is to provide profound attention, each essay focused on some apparently small thing that, when examined deeply, reveals vast meaning as it may connect to the heart of our personal lives or to evolutionary history going back millions of years, all that led up to the existence of the object being examined.”

Walter Cummins, review of Hidden Cargoes in the California Review of Books

“Two collections of literary essays by expatriate Irish writers have recently impressed me. Maggie O’Farrell’s best-selling I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death (2017) and Chris Arthur’s latest collection, Hidden Cargoes (2022) … Like Chris Arthur, Maggie O’Farrell was born in Northern Ireland (Coleraine), and he in Belfast. Both now live and work in Scotland, having left Northern Ireland for higher education… Both are making literary waves internationally, in O’Farrell’s case mainly in the form of the novel, and in Arthur’s case, in the more uncommon discipline of the literary essay… Arthur’s past in Antrim, on the shores of Lough Neagh, and in Donegal, continues to draw him imaginatively and literally back into the toils of Northern Ireland. Mostly the essays concern his deep ties to the natural world he knew so intimately as a child first there, and later in Wales and Scotland … There is much to admire in these agile poetic meditations, that share so much of their constructedness and their awareness, in particular, of how the cognitive and the verbal are interdependent. They cover a variety of engrossing subjects, sitting comfortably in a realm of poetic prose that is sui generis.”

Frances Devlin-Glass, review of Hidden Cargoes in the Australasian Journal of Irish Studies, Vol. 22 (2022), pp.160-162

“Arthur has a poet’s lyricism…Hidden Cargoes is a substantive work of research and creative analysis that also reads like a gentle musing on life by a favourite relative… [the book] needs time for its full appreciation, the kind of time we once had when the world stopped and we saw Blake’s ‘eternity in an hour’.”

Dymphna Lonergan, review of Hidden Cargoes in Tinteán, April 10 2023

“Arthur refers to the essays as ‘twelve exercises in paying attention;’ they embody a process akin to what the Russian Formalist critics called ‘defamiliarization.’ One metaphor Arthur uses for this is ‘the electricity of wonder that runs through everything.’ …. [His] writing … touches on many fields (autobiography, nature, philosophy, history) and his range of reading is equally broad. One of the delights of his essays is hearing about books one might otherwise not encounter. This breadth of scientific, philosophic and literary references reflects Arthur’s ability to take us on a journey into the many dimensions of reality that we are normally not conscious of. He provides a powerful example of what the essay form is uniquely able to accomplish.”

Graham Good, Review of Hidden Cargoes in The Dalhousie Review, Vol. 102 no. 3 (Autumn 2022), pp.428-430

“What Arthur’s Hidden Cargoes does … is surprise us with hitherto inconspicuous beauties from our own realities, beauties that we instinctively overlook because we are completely mechanised in the productivist redundancy of our lives. Arthur’s essays interrupt for a moment the passing of time so that we can grasp the cruel artificiality of these realities. He chooses fragments of our existence that we educated ourselves to assume as insignificant and invites us to analyse them with due calmness so that we can realise how unique and complex we all actually are”.

Fábio Wake, “A Flight from Reality: Chris Arthur’s Hidden Cargoes” ABEI Journal - The Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies, v. 24, n. 2, 2022, pp.113-116

“Chris Arthur’s writing is invariably marked by an expansive curiosity, an omnivorous reading life and spooling philosophical enquiries that begin with an attentiveness to the ordinary. His finely wrought essays are what challenged me to think about essaying as an activity outside the schoolroom, beyond those dry-as-dust abstracts and arguments of professionalised, templated writing that sometimes masquerade for life in the Humanities …. The range is eclectic and astonishing (an ear, an owl’s skull, a leaf, a scrabble game, a cigarette box, a vulture’s egg, a photograph) … Within these singular fragments, the vividly evoked quiddity of objects and also their hidden stories, is life’s redemptive vibrancy to hold against death’s finality… Readers will find their own treasures in these essaying journeys.”

Gail Low, review of Hidden Cargoes in Northwords Now, issue 44, Spring-Summer 2023, pp.36-37

“Said Ralph Waldo Emerson: ‘I cannot remember the books I’ve read any more than the meals I have eaten; even so, they have made me.’ Having read Hidden Cargoes, I have internalized Chris Arthur’s way of seeing the world — a ‘different strata of seeing.’ Or rather, I have been awakened to the way we normally perceive the world around us, ... 'a kind of seeing-without-seeing.’ … Arthur’s essays explore ‘the extraordinary nature of the ordinary.’ Their true subject is how we see (and don’t see) the world around us, how we perceive and experience. They are also about evolution, about history, about time, memory, ancestry and progeny, about lineage, adaptation, genetics, nature, and existence. Perhaps above all, they are about the limits and possibilities of language in helping us absorb life meaningfully. ... Often, after reading one of his essays, putting it down, and then walking across campus, I found myself musing, thinking, and reflecting with abandon. I hated being interrupted in one of his essays. I felt it diluted their power. When I read Arthur, I am sucked into his whirlpool of words — not drowning, but subsumed beneath the surface of his prose — only to be launched from that vortex, flying through the air like a soaring owl, ears humming with the sound of wind, eyes aflame. … Like Arthur, I have collected talismans of my own, humming with their own voltage and electric memories. A shard of ancient pottery, Oregon sand dollars, the branch of an olive tree, a deer antler. Looking at them now, I can begin to see the cargoes they carry that were previously hidden. Because of this, Chris Arthur’s is a book that I will return to again and again, to see what I might have missed the first time — to see if I can’t unpack any of its other hidden and precious cargoes.”

Isaac Richards, “Precious Cargo, a review of Chris Arthur’s latest essay collection,” Fourth Genre, August 30 2023

“This substantial collection of essays is a treasure trove of thought and ideas … William H. Gass has described how the essay form ‘convokes a community of writers’ and makes use of the writers like ‘instruments in an orchestra’. The essays in Hidden Cargoes echo this musical metaphor: they strike up a note, develop a theme and then amplify and diversify the originating inspirational material by introducing further meditation on, and exploration of the initial source — by citing the work of others, and reflecting on this…. In a world where the craving for instant gratification and instant “knowledge” is being deliberately promoted by algorithms cut off from community, nuanced and thought-provoking contributions such as Hidden Cargoes are needed more than ever. This is a generous intellectual offering, clothed in humour and lyricism, like a warm coat on a cold day or a magic cloak to shield us when we travel too near to the sun.”

Róisín Ní Ghairbhí, review of Hidden Cargoes in Studi Irlandesi XIV (2024), pp.285-6

“This is a sharp collection of essays in which apparently trivial observations become a springboard into sustained reflection and philosophical deliberation. The opening piece focuses on an owl's skull, and the associations it's come to have for the author: he recalls the wood where he found the skull as a youngster, and ponders the nature of owls and skulls in general. The term 'kist of whistles' describes the skull's former contents, its network of veins, nerves and capillaries: it's an oddly apposite metaphor that deepens the more you think about it, the brain likened to a nest of organ pipes that come alive with the flow of air. This sense of deepening significance is common to all the essays, as Arthur artfully unpacks his subjects, probing them for meaning and insight. In ‘Ear Piece’ he focuses on the ears of two travellers occupying the seat in front of him on a coach; in ‘Voice Box’ a picture on a cigarette box triggers speculations about his father's love life; in ‘Letters’ the rediscovery of an old Scrabble set has him pondering the force of words, and so on. While the style is discursive, he manages to sustain his focus, peppering his essays with entertaining trivia. An immensely enjoyable book.”

Review of Hidden Cargoes in the Rubery Book Award Shortlist 2023

Hidden Cargoes can be bought from:

"For the secret life of an essay is to lift the veil on the process of thinking, that most intimate of acts, to reveal not a thought, but thinking."

Patricia Hampl

Contents

- Introduction

- A Kist o Whistles

- Ear Piece

- Voice Box

- Leaf

- Letters

- Listening to the Music of a Vulture’s Egg

- Particle Metaphysics

- Blood Owls

- Pulse

- In the Stomach of a Termite

- Still Life with Witch-hazel

- Fitting In

“A Kist o Whistles”, the first essay in the book, focuses on the skull of a long-eared owl (Asio otus)

The lid of a souvenir cigarette box from a ship sunk in World War II (note that the blue background is made from butterfly wings). In “Voice Box,” this box is used as a kind of keyhole to look into the author’s father’s life, in particular the cruise he took in 1939 aboard the ship in question, T.S.S. Vandyck.

“Leaf” — an early version of which appeared in ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment (February 2018) — is a journey through the memories, ideas, and associations sparked by a single leaf fallen from a tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera). The photographs show (i) the autumn foliage of a tulip tree that was taken from Ireland and planted in the author’s garden in Wales, and (ii) a flower on the tulip tree outside St David’s University College library. Both trees are important points of reference in the essay.

A Griffon vulture’s egg (with coins to show scale) — found by the author in a junk shop in Ireland when he was a boy. It provides the starting point for a memoir/meditation that takes in aspects of Tibetan mortuary practice and philosophy, touching on aspects of “sky burial” and teachings about the bardo plane in the Tibetan Book of the Dead. The earliest musical instrument yet discovered, a Stone Age flute made from a vulture’s wing bone, is also brought into play.

Like many of the essays, “Particle Metaphysics” is a reflection on the way in which the ordinary and the extraordinary are intimately intertwined. In this case the focus is on a photograph of a street in Lisburn, County Antrim (the author’s hometown). The essay looks at how the photo can be read not only in a commonplace way (the physics), but also in a way that brings much more far-reaching perspectives into play (the metaphysics).

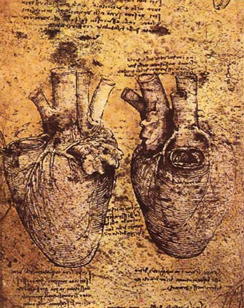

“Pulse” dissects a moment that’s framed by the simultaneity of three heartbeats that are briefly arrayed in a vertical line as a bus goes over a bridge: an oystercatcher’s heart, beating as the bird flies under the bridge; the author’s heart, beating as he sits in the bus; and a curlew’s heart, beating as it flies above bridge at the exact moment the bus is crossing it. The oystercatcher’s heartbeat becomes the main point of focus for the essay. Leonardo da Vinci’s question, “How could you describe this heart in words without filling a whole book?”, is one that’s also posed by “Pulse”. Da Vinci’s question is written on his famous drawing of a heart and its blood vessels (c.1513), held in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan.

An oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus) by Andreas Trepte.

A curlew (Numenius arquata) in flight, photographed by Charles J Sharp, sharpphotography.