What is it Like to Be Alive? Fourteen Attempts at an Answer

“Chris Arthur is among the very best essayists in the English language today. He is ever mindful of the genre’s long literary tradition and understands — as did his great predecessors — that the genuine essay is grounded in the imagination, in our quest for art and beauty, as deeply as is poetry or painting. Every young writer who wants to experience the creative possibilities of the essay must read Chris Arthur — it isn’t an option.”

Robert Atwan, series editor The Best American Essays

On the one hand, What is it Like to be Alive? is — quite deliberately — a varied collection that displays a stimulating diversity of content. On the other, the essays all address one question. Their points of entry may be very different, but they all soon lead into the same territory. If that territory had to be given a name — beyond simply saying it’s where the question “What is it like to be alive?” is considered — perhaps Alexander Smith’s “the infinite suggestiveness of common things” might be pressed into service as a description. Whatever we decide to call it, this is somewhere that’s attuned to notes beyond the hum of the quotidian. Each of the book’s fourteen essays starts from something ordinary. But what’s easily dismissed as unremarkable soon reveals threads that lead to destinations that are astonishing. Exercises in seeing beyond the obvious, all of the essays look into life’s mirror and offer their account of what they see there, shimmering elusively behind the obscuring immediacy of surface reflections.

In What is it Like to be Alive? readers are invited on a journey through some very varied territory. The “fourteen attempts at an answer” touch on:

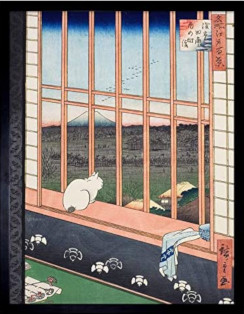

- The plight of prostitutes in seventeenth century Japan

- Watching ferrets in twenty-first century Wales

- The sense of existential absurdity maps can spark

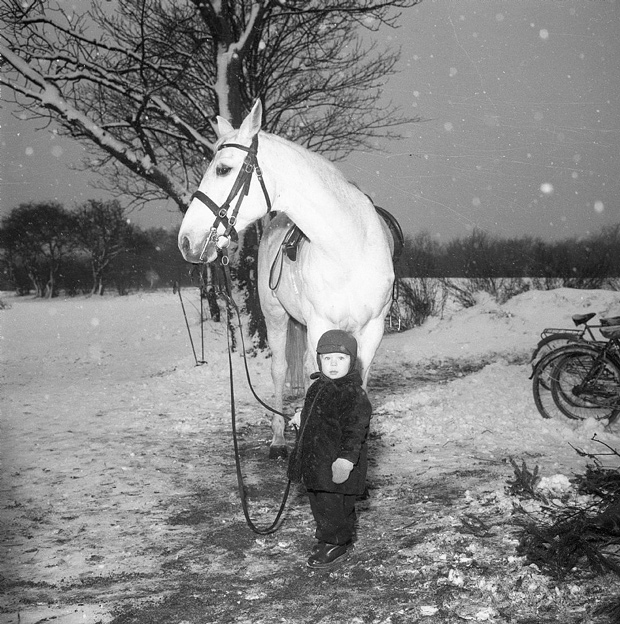

- A photograph of a little boy with a horse, taken in Sweden in 1958

- How best to approach knowledge of the Holocaust

- Different ways of seeing the statue of a controversial Irish warrior

- Aspects of a ninth century Pictish burial site in Scotland

- Creativity and ageing

- Europe’s smallest bird, the goldcrest

- Time’s scale as evidenced by a patch of lichen

- Problems and possibilities in retrieving childhood memories

- The importance of transitions

- The cargo carried by an ordinary moment

- Thoughts of mortality sparked by memorial plaques on park benches

What is it Like to be Alive? is named as one of the “10 Best Books of 2024” by the California Review of Books.

An extract from the book’s Introduction

… The essay that provides my title was pivotal in supplying the cognitive coagulation that drew the book together. It helped me to see the bloodline of ideas snaking through the individual essays. This creates the relatedness that makes them a family. My guiding question brings sufficient focus to avoid accusations of assembling a miscellany of unrelated items, but it’s not a strict enforcer of uniformity and order — such things are anathema to essay writing. Instead, the question acts as a lightly drawn emblem; it traces out a genetic watermark of belonging. In response to it, I’ve ranged over a spectrum of ideas. The value of asking “What is it like to be alive?” lies not so much in the specifics of any of the countless answers that could be given as in the space for reflection that it opens up; the way in which thinking about it attunes the mind to notes that can be missed if we only listen in the register set by our everyday preoccupations.

What is it Like to be Alive? is, unashamedly, an essay collection. That means it’s not bound by the kind of linear progression that some books follow, plodding their way, step by predictable step, from introduction to conclusion. The modus operandi of the essay is less regimented, more mercurial. Each of my fourteen attempts at an answer is independently intelligible on its own terms, rather than being a fraction of some wider calculation. Each essay is obedient not to any overarching plan but to the dynamics of its own unfolding. In putting them together as a collection I don’t want to pretend they offer a unified narrative, or that one follows logically from another. Cumulatively, the essays reinforce and reiterate each other’s concerns. And I like to think that, read together, they’ll lay upon the reader’s mind more forcefully than any on its own could manage the cadence of the voice behind them. Hearing that voice is close to the raison d’être of this genre — for “At heart,” as Graham Good puts it, “the essay is the voice of the individual.” I’ve arranged the constituent essays in a way that I think maximizes their reciprocity, but that doesn’t mean the book needs to be read in this — or indeed in any — order.

The epigraph, from Mary Oliver’s marvellous poem “Bone,” [see below] is not meant to suggest that I’m on some sort of religious quest, or that I give credence to the simplistic sense of soul that sees it as a kind of homunculus inhabiting our flesh, an ethereal essence within our lumbering corporeality. I see it rather as convenient shorthand for precisely what is sought in explorations sparked by asking questions like “What is it like to be alive?” It’s a term that indicates a realm beyond the commonplace where a sense of wonder at existence blazes, accompanied by amazement at our fleeting sentience. Without wishing to map the relationship between soul and language, I agree with Sven Birkerts that there’s significant linkage between them. He puts it nicely when he says, “Language is the soul’s ozone layer and we thin it at our peril.” Whatever else it achieves, I hope What is it Like to be Alive? provides some robust and enriching thickening.

The book’s epigraph, from Mary Oliver’s “Bone”:-

Understand, I am always trying to figure out

what the soul is,

and where hidden,

and what shape –

Reviews

“By any reckoning, Arthur has set himself an ambitious task. Throughout the 14 essays, he attempts to address the question of the book’s title through astonishingly diverse ruminations…Yet common themes emerge as Arthur’s essays deepen the mystery of being alive. The question mark in the title is important: to read What is it Like to be Alive? is not to get better answers: it is to get better questions … In following Montaigne’s example, Arthur’s essays are profound without ever being pompous. In a world where deceptively simple answers to deeply challenging questions are too quickly offered, it is a delight to read deeply challenging answers to a deceptively simple question.”

Eoghan Smith, “The Mystery of Being Alive”, The Irish Times, September 21 2024

“Despite the seeming implication of Chris Arthur’s title… he is not seeking an existential generalization about an abstract ontological question but rather exploring what living means for particular people at a particular time. Arthur is far from solipsistic in this quest. His concern is not limited to asking about the singular nature of his own living, his unique life. Instead, he wants to know what being alive is or was like for people in general, some his contemporaries, some who existed many centuries ago. Even beyond humans, he considers creatures like the tiny goldcrest birds and what it means for a human to connect to their life patterns. The words of John Muir explain his inability to limit his subject to himself: ‘When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.’ Being alive is a collective experience… To be alive for him means caring about other people and what being alive means for them. His examination of their circumstances may reveal a truth about them that he alone grasps, that may have escaped the person he thinks about so deeply, whose situation is a splinter that festers deep under his skin. Those situations considered in these essays explore empathy for a young woman haunted by the Holocaust, a long-gone Japanese prostitute in a city then named Edo, neighbors on a street in Wales, children surrounding him in a class photograph. What it means to be each and all of them, how such a variety of human beings confront the specifics of their existence. Arthur is a seeker who wants to know because their lives are inseparable from his: ‘In putting words on a page, in crafting my sentences together, I’m hoping to better understand—to mark and celebrate, commemorate—whatever aspects of my time here happen to catch my attention. To explain, for me, what it was like to be alive.’”

Walter Cummins, review of What is it Like to be Alive? in the California Review of Books

“Having read and reviewed multiple collections of essays by Northern-Irish-born essayist, Chris Arthur, I definitely qualify as a fan. I cherish these essays for their literariness and groundedness: they are an invitation to get off the spinning earth and take a long, slow look at life. His subjects are quotidian, but his meditating on them makes them expressive of different intensities of the sense of living through the senses, with the pleasurable engagement of the brain… The transience of human life is something that Arthur returns to throughout this collection, whether it be his meditation on the shards left by the Pictish population buried in Hallowhill near St Andrews, Scotland, or the garden bench plaques in his local Botanical Gardens. He loves to play with long and short perspectives of time and space to activate his ‘compound eye’, and his sense of ‘absent presence’… Best of all, the essays enact an intelligent interrogation of certainties and an invigorating sense that uncertainties are what we live with habitually, and that this may be a way of being more alive than otherwise.”

Frances Devlin-Glass, “Mercurial Meditations on Life and Death and the Everyday”, review of What is it Like to be Alive? in Tinteán, October 10 2024

“His prose is thoughtful and open with its personal anecdotes and self-reflection…it implores us to be curious, continually asking questions and searching for answers in life’s ordinary moments.”

Kaitlyn Denton, review of What is it Like to be Alive? in World Literature Today, July 2025, p.89

“Rather than starting out with a conclusion and then seeking the best way to order and transcribe it, Chris Arthur’s essays seem to record how the medium of writing itself — the process of naming and structuring through words — reveals previously hidden significance to both author and reader. Arthur, you get the feeling, isn’t writing to deliver pre-conceived assertions — he is writing to think…. What allows us to be transported by Arthur’s writing — to be carried from the specifics of his own history — is the precision of his language, which seeks always to find the bigger picture. The process of essay writing, perhaps, is to be in a medium which carries its practitioner closer to the thing at hand; subject and object are in the same space — co-exist in the text. Arthur achieves this by an openness to the objects he encounters in his particular journey. Describing them reveals that they are emblems of something bigger than his own place and status in the world.”

Graham Johnston, review of What is it Like to be Alive? in Northwords Now, Summer-Autumn 2025, pp.33-34

Albert Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus (1942) – a treatise centred on the question of suicide – hypothesises that the meaning of life is essentially what prevents us from taking our own… Chris Arthur, in What Is It Like to Be Alive? Fourteen Attempts at an Answer addresses a similar problem from an entirely different angle. Rather than confronting the contentious question of life’s meaning, he turns instead to the more tangible subject of the experience of living, examining everyday incidents which, despite their apparent triviality, prove rich in concealed meanings about the sheer accident of worldly existence. Arthur’s meditation on living is thus tied not to an ontological, but to a contemplative question – one grounded less in a verb than in a predicative adjective, or perhaps a preposition: What is it like to be alive? or What is the experience of living like?... A conventionally academic mind might attempt to answer this through some formulaic synthesis – a universal response designed to provide closure – but Arthur allows himself instead to drift imaginatively. The result is not a definitive conclusion but a personal reverie. … Reprising the approach he adopted in Hidden Cargoes (2022), Arthur scrutinises a series of seemingly insignificant moments and objects to extrapolate new perspectives on his own encounter with the world. From introspective musings provoked by old photographs to speculative reflections inspired by the instinctive behaviour of wild animals, his essays delve into the almost imperceptible threads that weave the intricate fabric of lived reality.”

Fábio Waki, “A Flight into the Past: Chris Arthur’s What Is It Like to Be Alive? Fourteen Attempts at an Answer”, Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies 27.1 (2025), pp.273-276

One of the essays in What is it Like to be Alive?, “Caging the Minute”, has James McIntosh Patrick’s painting “The Tay Bridge from my Studio Window” as its principal touchstone. The essay and painting are referenced in Ben Howard’s “Decent Ordinary Life”, one of his monthly columns on Zen meditation in his “One Time, One Meeting” blog. Howard offers some illuminating comments comparing aspects of McIntosh Patrick’s painting with Vermeer’s “View of Delft.”

“The essay has a knack for disturbing platitudes, questioning the accepted and rethinking the known.”

Mario Aquilina

Contents

- Introduction

- A Lament for Tama

- Ferret-Watching in Brynsteffan

- Snowglobe Coordinates

- What is it Like to be Alive?

- Splinter

- Nicholson’s Horses

- Images of Hallow Hill

- Picturing the Day

- Learning to See Goldcrests

- Litmus Test

- Remembering Stranathan’s

- In Transition

- Caging the Minute

- Benchmarks

“A Lament for Tama” makes reference to this woodblock print from Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

The book’s title essay focuses on “A little boy with a horse in winter, 1958. Sweden,” a photograph by Anders Hilding (1937-2020)

“Nicholson’s Horses” features this statue of John Nicholson (1822-1857), which stands in the centre of Lisburn, a city located eight miles southwest of Belfast. The photograph is by Manfred Hugh from Wikimedia Commons.

One of the items mentioned in “Images of Hallow Hill” is this seal box. Made of bronze and “millefiori” — meaning “thousand flowers” — a technique of using coloured glass, this beautifully worked artefact lay for 14 centuries in a child’s grave before being found by archaeologists.

“Learning to See Goldcrests” focuses on Europe’s smallest bird. This photo of a goldcrest (Regulus regulus) is by Ron Knight (taken from Wikipedia Commons). The essay suggests that: “If we’re to grasp what a goldcrest is, we need to pack a great deal more into its name, ensure the range of connotation that it carries is extended so that it echoes with more than a few of the obvious visible features it possesses… the name hints at something fluid, a glittering filament that spans a massive temporal distance, ancient yet still dynamic; a mercurial rivulet of life.”

This old school photo provides the starting point for “In Transition”.

“Caging the Minute” makes reference to “The Tay Bridge from my Studio Window,” a painting by James McIntosh Patrick (1907-1998). Patrick was one of modern Scotland’s most popular landscape painters and an artist closely associated with his native Dundee.

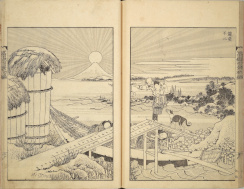

“Picturing the Day” refers to this image, from Hokusai’s One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. It’s sometimes referred to as “Fuji as Mirror Stand” — because the round disc of the sun is seemingly held like a great circular mirror, resting on the mountain’s summit.